I’ve got two things to talk about today and they’re both sort of related. The first thing is about getting to know your favorite photographers better, but also why to not put them on a pedestal. Sort of. You’ll see.

And the second thing is about questions. Sometimes they’re annoying, but we need to be cool. I’ll explain why, but it’s basic human empathy.

Kill Your Idols (To Love Them More)

In punk rock, there used to be a saying “Kill Your Idols”. I think Sonic Youth made it popular, but it definitely existed before them. Above the many tenets and contradictory notions in punk rock, “kill your idols” is something that everyone generally agrees with, but almost nobody actually does.

Many of us in the punk scene, ignored the mainstream and focused on local scenes and independent music. While this is something that probably should be transferred into the photography scene, that’s not exactly what I’m talking about.

There are some photographers who seem to exist outside of time. Take the most famous photographer of them all: Ansel Adams. His career spanned decades and his most well-known photographs – those taken in our National Parks – have little obvious connection to a specific era. They might have been taken yesterday or 100 years ago.

We know some of his pieces so well that it’s hard to envision a life without them. They are a part of us, a part of American heritage. They have always existed and always will.

Because of this, taking Adams’s work as a whole is difficult. Where do we start? Even coffee table books containing hundreds of his photos disperse them almost randomly, with little thought given to the journey he was on, focusing instead on how these photos look to us now.

This makes sense, since the audience for these books are people who aren’t photographers and aren’t necessarily interested in the breadth of Adams's work.

I’m using Ansel as an example we can all relate to. But this is true with most photographers. And especially true with photographers not as well known as Adams.

Maybe you’ve come across a photo by Imogen Cunningham or Diane Arbus or Alfred Steiglitz or anybody, really, and, while you liked the photo, placing it within a larger context of their lives or even history in general is difficult. Often a date will accompany it, but that means almost nothing to us.

We might be able to understand this better when thinking about music. There are bands, like Parliament/Funkadelic, XTC, Springsteen, or Zappa, whose discographies are massive and their songs seem to exist, like the photos of Ansel Adams, apart from time.

You might have heard a few Sinatra songs, maybe “Come Fly With Me” or “My Way” and wanted to hear more, so you listened to one of the many Greatest Hits albums. But even that, like most photographic coffee table books, gives you a fine overview, but fails to place the songs into the context of Sinatra’s discography, his career, his life, and our larger history.

I’ve done this with a bunch of bands as well. I mentioned my friend Brad in the last episode. One day, he dropped an XTC CD in my hand - Apple Venus Vol. 1. I listened to it and loved it, but didn’t really understand how a band could get to this odd point. So I started at the beginning, listening to their first album, their second, third, fourth, their entire discography through to their final album. It was wonderful to listen to a band create and change and reinvent themselves over and over.

This is absolutely applicable to photographers. Seeing what an artist first creates shows us where they’re coming from. Seeing how they change, shows us how their lives and influences have affected their work.

And I do think this matters. Maybe not to the general fan of photography, but to a photographer working on their own pieces, trying to find their voice, trying to keep going, it matters.

We never look at dates on photos unless the photos are documentary in nature. We just see a photo and it exists. Maybe it always existed. We don't know which came first or what came second. We don't know what came before or what came after. We might enjoy the photos, but knowing the context helps us understand the artist.

Understanding a photographer’s full body of work, its chronology, and (to maybe a lesser extent) the photographer’s biography, helps us, as photographers, put our own work in the larger light of our lives.

But I also think there’s a better reason to understand this context. Many photographers, from Adams to Cunningham, Sally Mann to Dorothea Lange, seem like gods to us. There is a sort of pantheon of photographers who seem above us, beyond us, untouchable.

Humanizing the popular photographers we like might go a long way towards this killing, essentially killing the idol part of our idols. Tearing down that pantheon, erasing the line between the greats and ourselves.

Because, of course, they were humans just like us. They were photographers just like us. They had some beautiful moments, and some crashing disasters, just like us. They were obviously good at their craft, but so are we. The line separating us from them isn’t nearly the wide gulf we often believe it to be. Our work is as important as theirs. To ourselves, our own work should be (and is) more important.

Learning about the photographers we like humanizes them. If we stop seeing them as celebrities, as famous people apart from us, it allows them to become more human, and their work more relatable. Seeing their most popular photos alongside their mostly-ignored photos helps us understand our own hits and misses. Seeing their journey helps us understand our own.

When we get into slumps we can see that these other artists have too. We know our own chronology. We know the shit that we produced early on. We know the successes, the beginner's luck, the bad rolls, bad shots, and general fuck ups. We often allow our own mistakes to define us, control us. But all the photographers we admire went through that too. Maybe their fuck ups are lost to antiquity, but they existed. They were there.

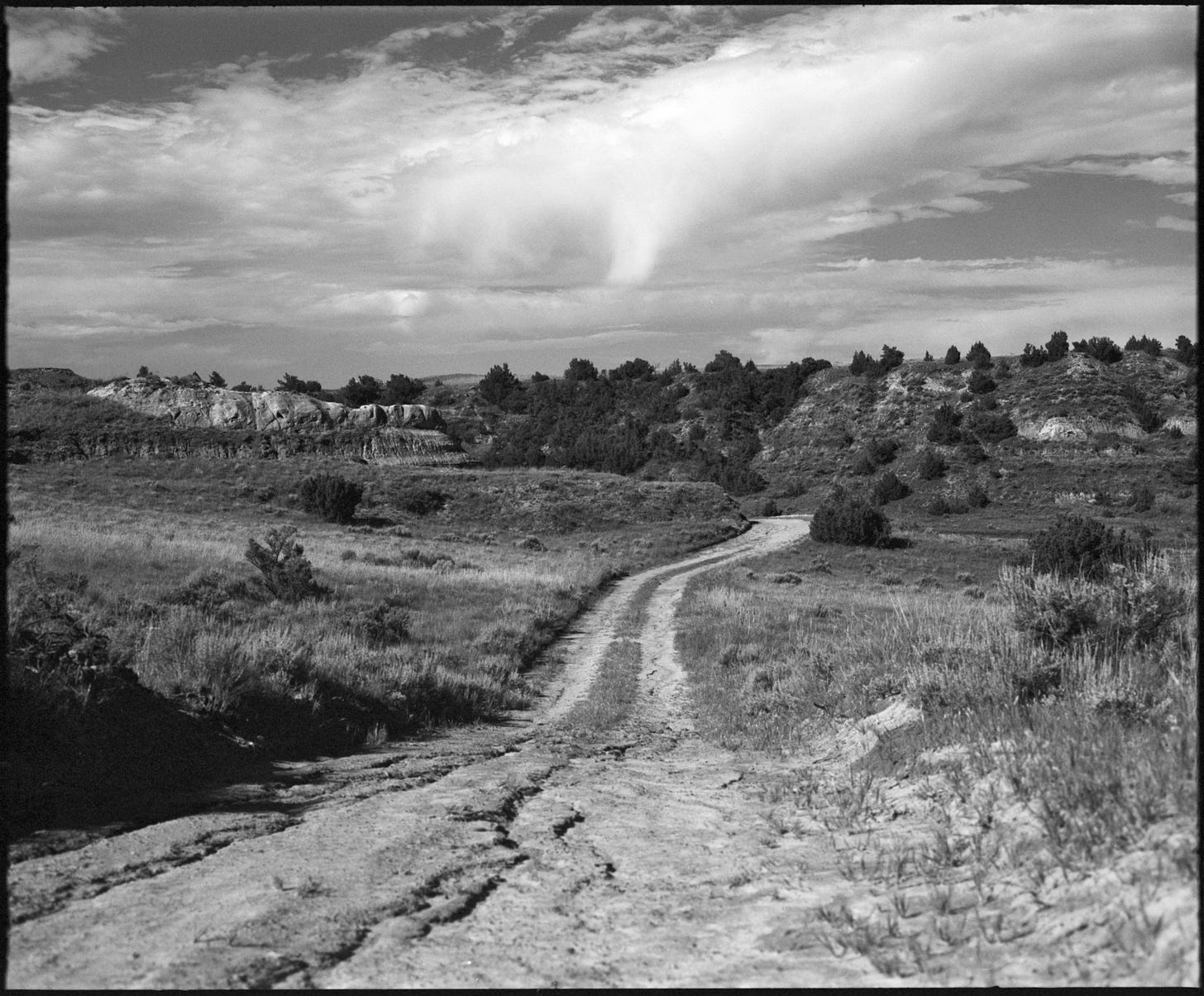

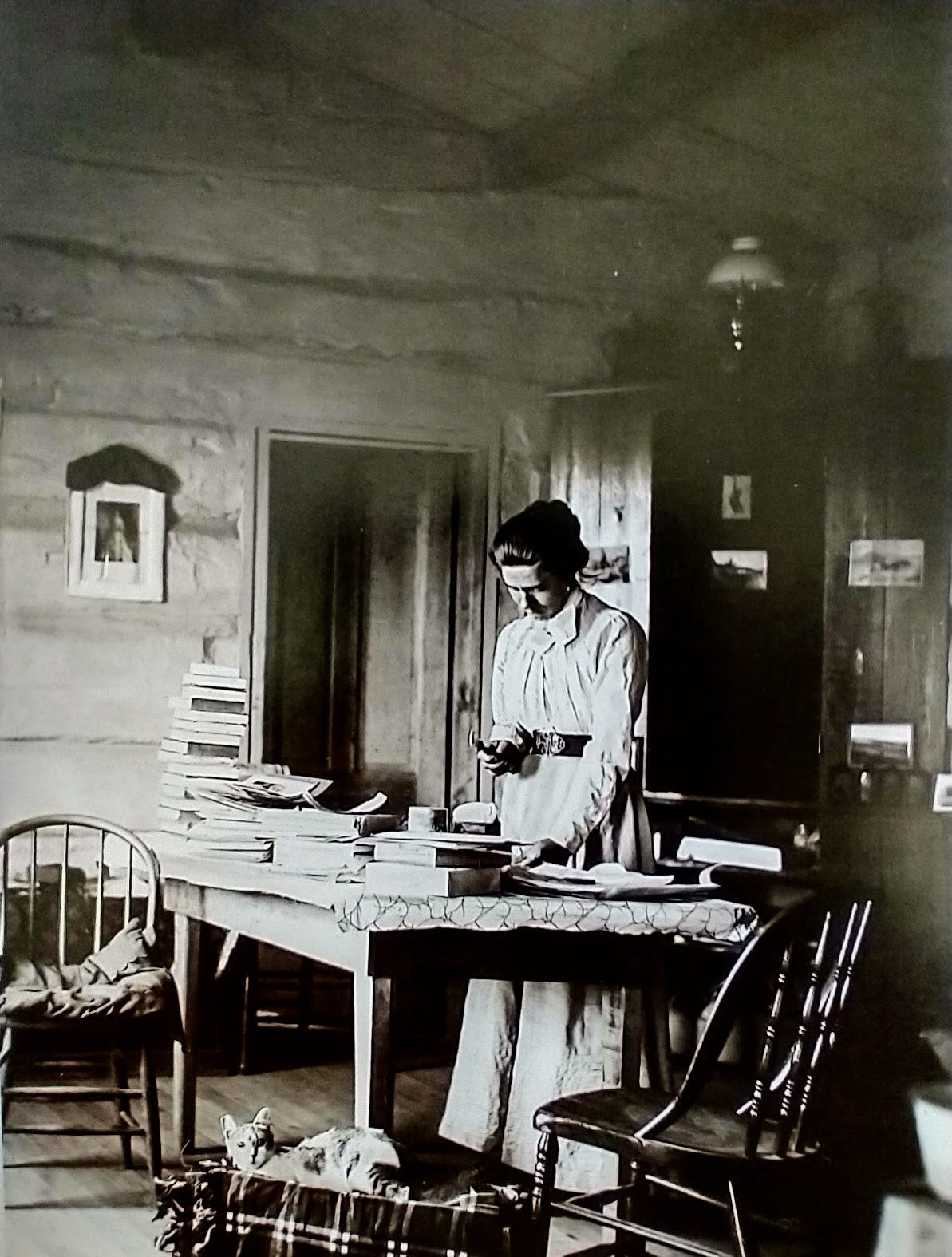

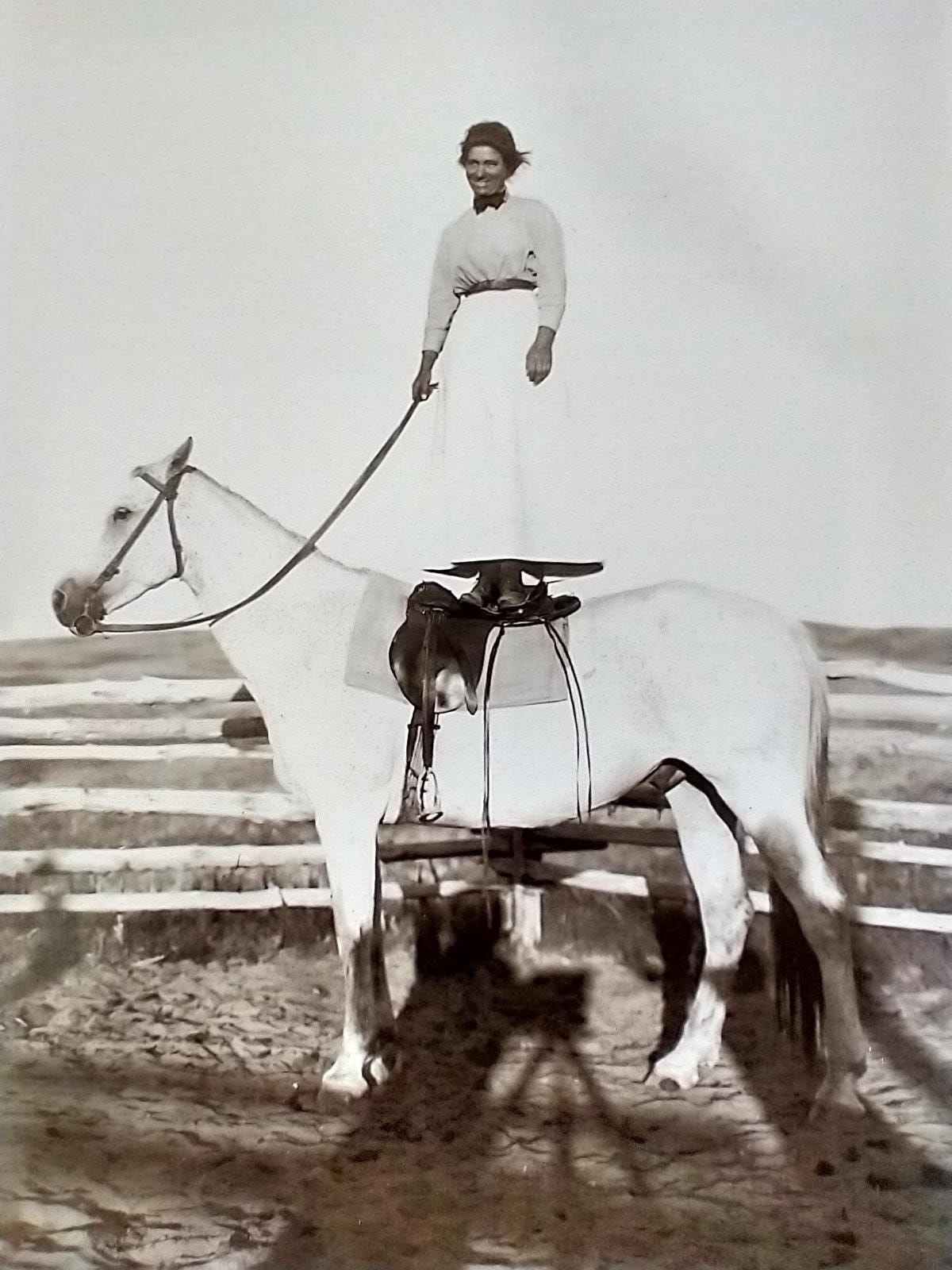

There’s one event in my life that solidified this belief for me. You might remember the name Evelyn Cameron from my previous podcast. She was a photographer who worked in Montana in the late 1800s and early 1900s. She photographed the local landscapes and the ranch life of eastern Montana. I don’t remember how I got into her, but I had a book that told a brief sketch of her life and then a random scattering of her photos.

The next summer, I traveled to Terry, Montana, where there are two museums and galleries dedicated to her. I visited the galleries and saw prints she made herself, some of her clothing (including her famous pith helmet) and had a wonderful time.

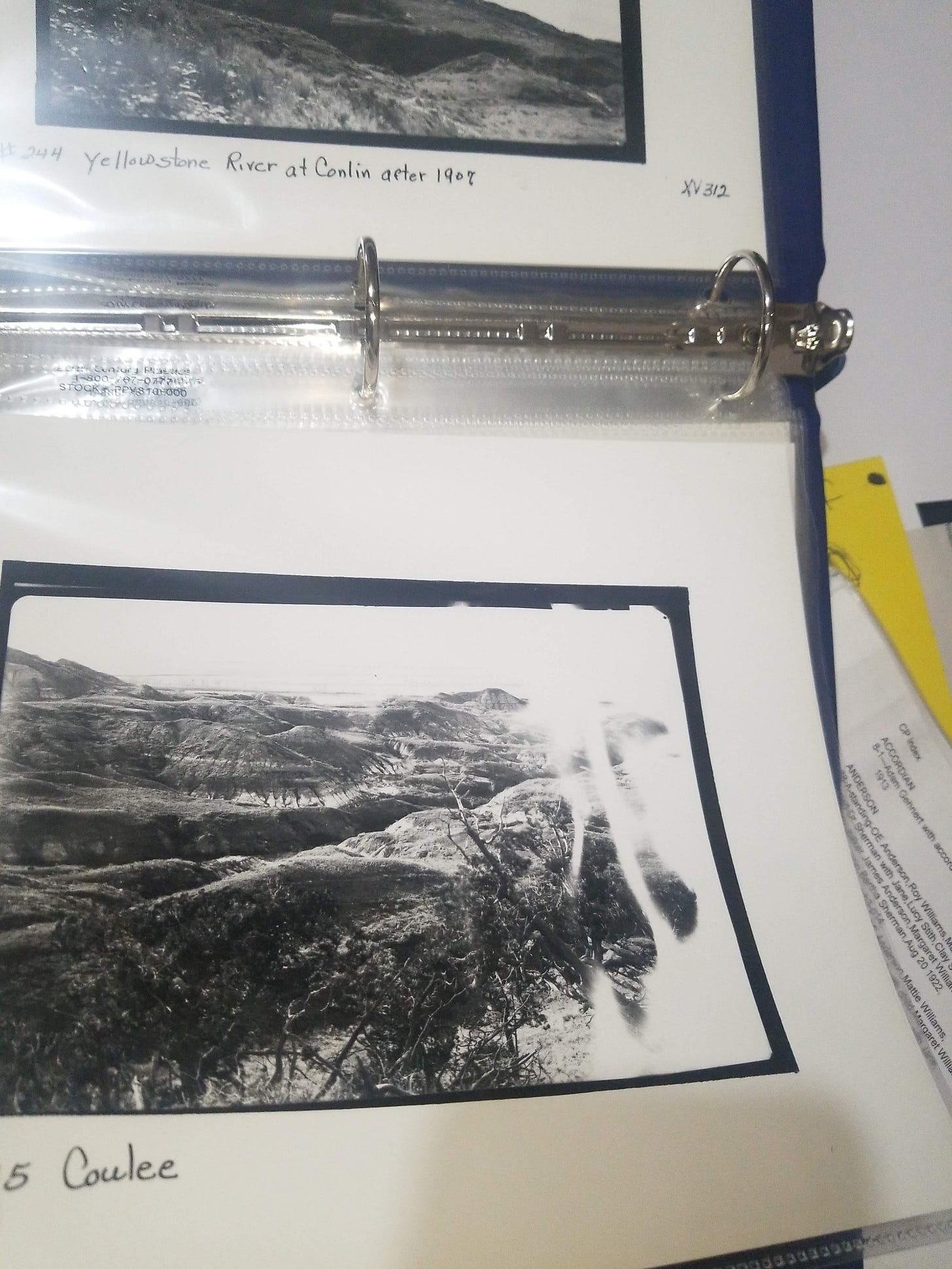

The main county history museum, located in an old bank, has almost nothing of Cameron in it. Except, in the vault are contact prints made directly from all 700 or so of her glass plates. They were cataloged and kept in binders (the actual plates, along with her Graflex camera named Lexie, are in the state museum in Helena).

The person watching the museum allowed me to spend as long as I wanted with these contact prints, all 5x7 printed on 8x10 paper (I think I’m remembering this correctly).

The photos contained in the book I had and galleries I visited total maybe 100 or so. It’s a small fraction of her archive. But now, that entire archive was right there before me.

This was my first trip shooting 4x5. It was the same trip as the Utah Canyon mishap (one hell of a trip, right?). So I was making a slew of rookie mistakes all over the place. I was forgetting to close the shutter after focusing, I had light leaks from bad holders, I missed focus, had bad composition.

And as I leafed through Evelyn’s archive, I saw these same mistakes. She had some bad holders too. She overexposed sometimes, she missed focus, sometimes her composition was off and she retook the photo. I recognized the same developing mishaps that I was making too.

Suddenly, this amazing photographer, this artist who I had placed on an untouchable pedestal, was human. She was still a brilliant photographer, but she also fucked up a lot, just like I did. And she wasn’t doing this only at the beginning of her work. All throughout, she made mistakes, just like we still do.

If someone would have asked me before seeing her archive if I thought Cameron was some untouchable idol, I would have said no, of course. Intellectually I knew she was a fallible human. But knowing something intellectually and seeing the evidence of it right there before you are two different things. That day, I actually realized that the photographers we look up to are less up and more by our sides than we tend to believe.

That day, I killed my idol. But I also drew closer to her. I saw something of her work that so few have seen. I went from really liking the photography of Evelyn Cameron to falling in love with her work, the town she called home, and the landscapes she photographed.

And I realize this experience is rare. We are almost never afforded this opportunity. But with some of the more popular photographers, archives are available, and if we can, we should arrange to visit them.

In most other cases, we might have to do some digging and some used book buying. We might have to read some biographies and begin making a sort of archive ourselves, noting the chronology of their popular photos and digging deeper to find less famous shots (or even mistakes) to place around them.

This is a daunting task and a pain in the ass. But in quite a few cases, there are retrospectives and anthologies that are arranged chronologically with hefty bios for introductions. These bios usually reference and contextualize the photos, essentially doing our work for us. All we have to do is look.

Unfortunately, a lot of books, even anthologies, don’t put the photos in chronological order. There’s an amazing and huge Anne Brigman book that is one of my favorites to just flip through, but the photos have no relation to her chronology. Fortunately, there’s another book, not nearly as well produced, that does this.

I realize this seems sort of nerdy, much more academic than artistic. And it is. But it also helps us understand our own work. And if we really wanted to get academic about it, we could also look at their influences. We do this in music. I listen to a lot of Sinatra, and recently learned that one of his biggest influences was Billie Holiday. So now when I listen to Miss Day, I listen for the bits that Sinatra brought forward.

And I’m definitely not saying we need to do this for every photographer we enjoy. But it really is beneficial to try this with at least one you already know pretty well. Find a biography and start matching up photos to points in their lives. Try to find one with a long career, maybe one with different phases or periods. If you get really lucky, there will be entire books published about their specific periods, like Lee Miller’s surrealist phase or Edward Weston’s early years or Man Ray’s Paris years. It’s likely the authors will have contextualized this part of their work for you. You get to learn and hardly break a sweat.

Studying and reading the biographies of photographers really isn’t about learning what they did in their lives. Sure, their antics can be a fun context (especially someone like Margeth Mather), but really it’s about learning when and, more importantly, why they took the photos they did.

It’s not that I don’t care about their lives and their exploits, but mostly I just want to know how their lives influenced and affected their work.

Then we can look at our own lives and compare similar situations and see how those situations have affected our own work. Maybe we’ll notice things in our photos that we didn’t see before. Maybe we’ll see our own work in a different light.

Learning all we can about our favorite photographers demystifies them, it returns them to our level, to reality. These photographers existed, like that asshole Morrisey sings in “Cemetery Gates,”with loves and hates and passions just like mine. They were born, and then they lived, and then they died.”

There’s more to their lives, of course, just as there’s more to ours, but to put it plainly, they’re just people. They’re just like us. We’ve made them idols in our minds, and that notion should be killed. But we don’t kill our idols by boycotting the photographers we love. We do it by humanizing them, drawing connections from their lives to ours, by seeing their mistakes, their early work, their middle work.

We do this by putting their photos and their lives into a larger context. We do this by killing the idols we’ve made them to be and celebrating the beautifully flawed humans that they were.

Now it’s time for the second segment which is only very tangentially related to the first segment. Okay, here we go…

Crazy Kid Stuff

As photographers, we get asked a lot of questions from other photographers. From “what lens do you use?” to “what’s your favorite emulsion?” When we share a photo, the questions are almost never about the subject or photo itself, but the equipment we used to take that photo.

Today I was reading 3 Shades of Blue by James Kaplan, which is about the recording and history of Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue album. In it, Kaplan related a story about when John Coltrane (who played on the album) and a friend and fellow sax player, Benny Golson, met one of their idols, Charlie “Bird” Parker.

On a June night in 1945, John Coltrane and Benny Golson went to a Dizzy Gillespie/Charlie Parker show at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. This was their first time seeing Charlie Parker and each had a different reaction. Though Coltrane played it cool, Benny, as he explains here, did not:

“After that concert was over, we went backstage, like kids do, and got everybody’s autograph. It was an evening concert and Charlie Parker was going over for the first show at a place called the Downbeat. And so John and I were walking up Broad Street with him, and John was saying,‘Can I carry your horn for you, Mr. Parker?’

“I’m on the other side saying ‘What kind of mouthpiece do you use? What kind of reed do you use? What strength reed do you use? What is the make of your horn?’ This crazy kid stuff, and he was telling it all and I thought I was getting the real lowdown.”

These questions are crazy kid stuff. In a very real way, it’s not that important. Just like asking what filters and film and even cameras photographers use isn’t important. The art of it all is the important thing.

But that’s difficult to talk about. What isn’t difficult to talk about are lenses, developers, specific chemicals in developers. All of that is easy and casual conversation. It’s mundane and broadly unimportant, but I get it.

And I do get it. I get these questions all the time. This is the reason why I share which camera, film, settings, lens, and developer I use. Because when I didn’t, I got asked that over and over. I’d always be cool and never really minded, but now many of the questions are answered before they’re asked.

Except I get other questions now – “which filter are you using? Which version of the RB67 do you have? Are you scanning your negatives or using a dslr?”

I’m still cool about these questions. Any of them, really. But I do lean more on the side of their unimportance. They are, as Benny said, crazy kid stuff. They’re the things you think to ask when you don’t know what else to say. When you just want some sort of conversation with a photographer (etc.).

I’ve been on both sides of this. When I was just getting into photography and trying to figure it all out, I’d ask these crazy kid questions too. I was often ignored or told it didn’t matter, which is a real dick thing to do. So now that I’m on the receiving end of these questions, I’m more than happy to answer them, just like Charlie Parker was more than happy to rattle off the answers to Benny’s questions.

But really, the answers don’t matter at all. If I use a deep yellow filter instead of a regular yellow or red, it doesn’t matter. If I prefer the RB67 Pro S over the Pro or Pro-SD, it doesn’t change a thing. If you found out that I like the original uncoated lenses over the C or K/L versions, your life should be no different than before. That is crazy kid shit.

Until it’s not. When the questions turn from what to why, that’s when things get interesting. If Benny asked Bird “Why did you change from a Tonalin reed to an Ebolin?” then it would be a conversation. But Benny wasn’t there yet. He wouldn’t have known what to do with the answer, let alone think of the question.

Beginning photographers are like that too. They don’t have the experience to ask the important questions. And that’s okay. As experienced photographers, we need to make sure we’re being cool with the new ones. We need to answer those crazy kid questions and nudge them onto something more important.

New photographers need to learn that even with the exact same camera, lens, film, developer, and scanning method, they’re not going to take the same photos an experienced photographer might. They need to learn to build their own style. And I think these crazy kid questions can be part of that.

What’s likely happening is that they see something in a photo that sparks something in them. Maybe they want to emulate that to an extent, but what should be encouraged in them riffing on that idea. They need to be encouraged to take that equipment or technique and make it their own.

And when they make it their own, when they find their style, their place, they’ll get these crazy kid questions too. And hopefully, because we were cool to them, they’ll be cool to the next batch.

Share this post