I had packed the night before - camera, film, water, food. I had checked maps, selected my trails, and committed them to memory. This would be an easy hike, I thought, but then recalibrated. I am out of shape, this is the first hike of the year (first hike in a year), and I haven’t felt great in months. This will be what it is.

It’s not that I didn’t care, but I had to get out. The winter and early spring of Seattle was suffocating me. The constant noise of cars, the echo of far too many voices, the monotony of concrete and asphalt and concrete was walling me off, brick by brick.

There’s a balance we try to strike as photographers between living in the moment and photographing that moment. It’s impossible to do both, though we often tell ourselves otherwise.

We lie to ourselves, saying that while we are experiencing the through the lens, it’s still happening and we are still fully present. We want so badly for this to be true, even when we’re not hiding behind the camera. Experiencing the moment without the filter of a lens grows terrifying the more time we spend behind it.

It was tempting to leave the camera at home, but of course I didn’t.

What I did was a compromise I made with myself years ago. Each hike, I make some vague attempt to carry my camera inside my pack. Of course, this runs antithetical to the photographer’s philosophy/film manufacturer’s marketing slogan of always having a camera at the ready.

This, I’ve found, allows me to experience the moment first, and then hide behind my camera. This also means not capturing some of the moments. But then, this is also a rule I end up breaking to no real advantage by the end of the hike.

With large format a pack is necessary. There’s really no other way to carry a tripod and camera that needs a tripod (as well as film holders) into the field. But I’ve also started doing it with medium format, lugging the boat anchor known as the Mamiya RB67 on my back.

When I see something worth a photograph, I sling off the pack, unroll the top, take out the camera bag, take out the camera, and shoot. This entire operation requires only thirty seconds or so. The lens is already on the camera, the film is already loaded. All I need to do is check the light.

The sun rose softly behind thick morning clouds as I crossed the Columbia River on Interstate 90. I had left Seattle hours before dawn and regretted not camping the cold night before. The light was dim and gray, and though I was there to photograph the spring wildflowers, I had brought enough black & white film to last the entire hike should the clouds fail to disperse.

Washington is known for its lush forests of firs and moss, its tall granite peaks, and glacial lakes. But that is almost never my destination. East of all that, on the other side of the Cascade Mountain Range, lies an almost prairie landscape full of sage and grasses intercut with seemingly inexplicable dry box canyons. It’s called the Scablands, and that’s an awful name for one of the most beautiful places I have ever seen. This is the shrub-steppe, a (nearly) desert grassland that covers nearly one-third of the state.

While a few trees dot the landscape – mostly the invasive Russian olive tree – the rolling hills are covered with sagebrush, a slow-growing shrub whose leaves smell of camphor and mint. When it rains, the air fills with this scent and everything in the world seems perfect, even though it really, really isn’t.

When I arrived at the trailhead, there were more cars than I had ever seen there before: fifteen. Maybe sixteen. Had my spot been blown up? I wondered, reminding myself that this wasn’t my spot, that I’m only here a few times a year. This is public land, and it’s ours. But still, that’s a lot of cars for a place three hours from Seattle. I parked, double-checked my gear, took a long drink of water, and started down the trail.

The hike was at a place known by a few different names. Most commonly, it’s called Ancient Lakes – a misnomer we’ll come back to. But it’s also called Potholes Coulee, and has been for nearly a century. This is a state wildlife area known as the Quincy Lakes Unit, part of the Columbia Basin Wildlife Area.

The main features, apart from the lakes, are two half-mile wide canyons running parallel, east and west into the Columbia River, for two miles with a thin spine separating them. From space, they look like a giant had pressed two fingers into the mud. The north canyon, Ancient Lakes Coulee, is the most traveled and visited. It’s the easiest to get to and has several small lakes inside it. The south canyon is Dusty Lake Coulee. They are not mirrors of each other, but hikers rarely do both.

But I would do neither this time. Over the years, I have explored and camped in both. I have walked in from the same trailhead, level with the floor of the coulees. And I have also scrambled the 250 feet down the side of the coulees from the top. I have hiked and photographed the overlooks, side canyons, wetlands, and oddities of this place for the last fifteen years.

Though the coulees themselves weren’t where the trail was taking me today, my first stop was a photo I have wanted to retake for years. Nothing was wrong with the original one. Or the one I took after that. But I wanted to see what I could do with it again.

A main trail – actually an old ranch road – leads you across the wide mouths of both coulees, here nearly a mile in width. Along the way, several trails lead you inside the coulees, with various branches splitting off here and there.

I tramped past the first main trail off, and then the second, cresting over the crumbled remains that divided Ancient Lake Coulee from Dusty Lake Coulee. From here, I looked east along the tall spine left standing. These were sheer basalt cliffs with columns like the Devil’s Fence Post or Giant’s Causeway. But they were here, unheralded and unnamed, tucked into the cliffside with some small sunlight piercing the clouds and showing their tall shadows. Looking a mile across to the other side, a small waterfall was lit up white by the sun, and it twinkled and shone. If I had time, I said, I’d visit it on the way out.

I backtracked some, returning to the trail into the coulee. My footprints were the only ones on it that morning, and I tracked over only the faintest of prints left in the mud some weeks before. This was the first warm weekend, more would be coming. But for now, it was just me.

What I was seeking was off-trail a bit, and I began angling away from the trail, moving through grasses, sage, and nearly-opened rock buckwheat flowers, stepping over tumbleweeds of invasive Russian thistle, until I found a century-old iron wheel stuck into the ground. What was left of its spokes was cut so the axle could be freed.

I don’t know what this wheel was attached to or why the wheel was left. I know nothing of it at all, finding it by accident as I roamed around a decade ago.

I slipped off my pack and removed the camera. I circled the scene a few times, deciding how to shoot it this time, forgetting how I shot it last, though maybe that’s for the best. When I reshoot a location, I try my best to forget how I shot it before. But I also want to photograph it differently, and so I try to feel my way into something new. Sometimes it even works.

The light was still dim, and I used 400 speed Ilford HP5 with a yellow filter to bring some small handful of contrast to the scene. Still circling the wheel, I shot several frames, including a close-up of a thistle branch. The sun cooperated by staying hidden, and I continued on, looking for the trail that would lead me lower.

If the coulees had flowing water, it would empty into the Columbia River, running perpendicular just a mile west of the trailhead. The land between the coulees and the river, 500 feet below, is a maze of tall, sharp outcroppings and dead-end narrow basins. Few trails lead down the various precipices, but I had found one that did.

The trail here was a well-cut walkway clinging to the side of a basalt cliff. Over the millennia, the cliff had shed, littering and piling thin rocks along its walls. Eventually, I thought, the cliffs will shed so much they will no longer be cliffs, but hills, steep and rolling. For now, though, walking over this uneven and precarious talus path, the view winding down to the river, still hidden in a canyon of its own, stopped me.

With the sun, still low and again behind clouds, the gray valley unfolded itself. The rocky path I was on descended to a landing lush with grasses and sage. As the cliff I was walking along faded away, another, opposite me, extended with various levels and shelves, themselves covered in grasses, leading to basalt walls and columns hundreds of feet high. Trails branched and combined within this small space.

Above me cried two ravens, flying side-by-side in the cool air. As they floated down into this little valley, towards the Columbia, one of the ravens turned upside down, tucked in their wings, and gave a quick and joyful “caw caw!” before flipping back and gliding with their friend. A moment later, the raven again flipped over, repeating the same call, and then back right. They did this several more times before flying back up the canyon, circling, and gliding back down again. As they escaped my view, I could still hear the upside-down “caw! caw!” echoing off the walls.

This is often seen as a mating ritual or a way to assert dominance, and both of those things might be true. But it’s also fun. Like most birds, ravens and crows fly to find food, to get from one place to another, for survival. But they also fly for fun. Ravens and crows play. I’ll often see my city crows sliding down roofs when it snows.

Taking some time to watch ravens in the wild is endlessly rewarding. They are intelligent, cautious, and shy, so if they see you as an unnecessary threat, they will leave you. But if you have patience and quiet, you can watch them for as long as they allow and your life will be all the better for it.

I didn’t photograph the ravens, I didn’t even try. This was a moment I wanted to experience myself, without the gauze of ground glass. Also, on a practical level, trying to frame and focus anything moving through the waste level finder of a Mamiya RB67 is a confusing, frustrating mess that not only results in no good photograph, but also succeeds in fully removing you from the moment. Part of being a good photographer is knowing when you’re not.

The grassy plain below was not flat like it seemed from above. This is a feature of this land that I will never grow accustomed to. Looking across any open space of sage and grasses reveals what seems to be a featureless flatland. However, when you make the trek across it, you rise and fall with the undulating ripples and hills, invisible just moments before.

I scrambled up some natural steps, between sagebrush and giant boulders left stranded before coming to a landing where the Columbia finally came into view, still hundreds of feet below, as if the river was falling with me.

By now, the sun gave a full view of the yellow and green landscape. The temperatures were rising, and I wanted to steal a small slice of shade before that too slipped away. To my right were the basalt cliffs, still reaching towards the Columbia, and to my left was a small outcrop of rock surrounded by the yellow blossoms of the arrowleaf balsamroot, a small sunflower which grows in bunches a foot and a half tall. Patches of these could be seen on the opposite slopes and shelves, but here was a small patch surrounding the dried skeleton of a sagebrush.

Since I was resting anyway, I went for the camera. With the light still coming and going, I went with a very expired Portra 400, shooting it at 100 and figuring it would all work out. The choice between black & white film and color is often one I struggle with, even when it comes to flowers. But on this day, there was no struggle at all.

The shadow of the formation, the shade whose shelter I was under, covered some of the flowers and part of the old sagebrush, but the rest glinted in their morning splendor, overlooking the grasses below. I took two shots and continued my walk.

Though I should not have been surprised, I lost the river behind a hill growing before me. This was a tall bench overlooking the final drop into the Columbia. With short breaths, I crested it and stopped.

The bench did not lead directly to the river itself, but sloped sharply before flattening out into a flood plain where countless boulders were strewn amidst trails leading to the water. A row of trees, their leaves newly green in the spring, lined the river, and between them, a few hikers had established camps. I could hear voices from below – the first I had heard since the trailhead.

There is a large part of me that hikes and photographs and travels for the solitude. I live in a city, and to visit a popular waterfall or overlook near the city seems ridiculous to me. I come to nature to escape the crowds of the city, not to meet up with them atop some ridge with a view of the entire Seattle metropolitan area. But that morning, the laughter and joy floated up with the breeze, and it somehow seemed fitting.

I could see no people, just a tent or two, but I photographed this view in both color and black & white, unsure which would relate the scene best. Looking at them now, I still don’t know.

The trail winding down to the campsites skirted a large washed-out gulch a few hundred feet wide. Crossing it, I expected to see layers of rock and earth denoting eras and the passing of time. Instead, the inside of this gulch and the inside of this shelf were a mix of cobble and sandy earth. Some of the rocks were basalt, which made sense, but many were of various colors and sizes, most worn smooth and rounded as if tumbled not just by some long-forgotten glacier, but by water.

This is one of the many stories of this land, all too involved to tell. But from here, you could see much of it. The basalt, then as lava, had flowed from fissures in southern Washington and Oregon. Here, it had flowed and then cooled 15 million years ago. During the ice age, 20,000 years ago, glaciers made their way south, coming close to Ancient Lakes, but never quite touching them.

Of course, at that time, there were no coulees and canyons. It was just rolling hills and grasses, much like the Palouse region in the far eastern portion of the state. But then the floods came, perhaps 15,000 years ago. Over and over, water burst from ice dams and from under melting glaciers, flooding all of eastern Washington, tearing away the loose basalt, creating channels and canyons where I now often photograph and hike.

Here in this gulch was the wash from those floods, now encompassed into a bar along the Columbia. The boulders below were carried both by the water and within icebergs. The entire Columbia River here and through the gorge to the Pacific was also largely carved out and deepened then.

All of this was so clear and plain here in the middle of this gray and ugly gulch. I crossed to the other side and to grass, made my way back up the shelf, and walked along its ridge. I was now off-trail again.

There’s something freeing about being off-trail. In the thick woods it can be dangerous, but here, with a clear view of everything in this world, it made me feel part of it all. I found a small coyote trail and went along it, noticing prints here and there.

I took no photographs as I walked a mile or so north. The soft grasses gave way to more rugged ground and sage, but I continued until I came up against a barbed wire fence.

I’m always a little hesitant to cross fences. I was fairly certain that it was public land on both sides, but I walked along it, waiting for a gate or an opening. In some time, I came to one – an opening where there once used to be a gate. This was public land after all. I knew there was an old ranch road that swung from the hills above and led down to the river. Once I found it, after a couple of miles of walking, I stayed with the ridge, following an older trace.

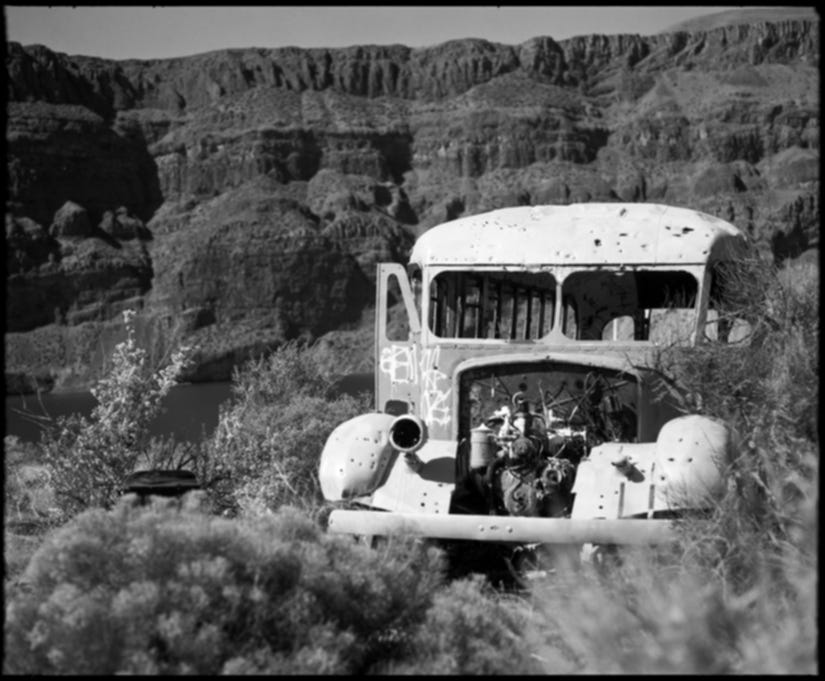

This brought me to a scene repeated throughout the deserts of the world: an old school bus left abandoned, spray-painted and gutted. I don’t know the story of this one. Maybe it was hippies who drove it down and couldn’t dig it out. Maybe it was a rancher who planted it there as a camp for his hands. This whole area was once a sheep ranch. Either is possible.

But here it sat, a school bus, stripped of everything, including the wheels and seats. The engine, coated in many layers of paint, stood open. The bus was a full-size late 1940s, early 1950s Dodge. Its windows were all broken out, and bullet holes pierced it on all sides. Generations of wasps had claimed it, so I didn’t enter, but poked my head inside. The seat had been removed and was sitting next to where a fire ring might have been.

I photographed it in color and black & white extensively. I had now switched to Fomapan 100 and finished off the Provia. In nearly every case, the color won out, and for the same reasons as the flowers - the yellow against the sage green and blackened basalt, the brown grasses and blue sky. There was a life within this color that black & white couldn’t translate.

With my last frame of Provia, I rested to change film and have my small lunch. I brought along a few rolls of expired Fuji Astia, a slide film that filled some perceived space between Fuji’s other offerings: the soft Provia and the intense Velvia. It was a line that didn’t last long, maybe 15 years. This had expired in 2000.

With age and how I develop my color film, I knew that there wouldn’t just be color shifts, there would be a borderline surreal representation of color. It looks back to a feeling I had when I first started photographing eastern Washington – I didn’t want to show how the place looked, but how it felt.

I ate my peanut butter sandwich and gathered my things. I tend to spread out when I photograph. With large format it’s the worst, but even with medium, even with only one camera, one lens, and two film holders, I can be a bit of a mess. I checked the ground to make sure I left nothing behind.

All along the hike, I had been taking quick videos with my phone and posting them as stories on Instagram. I thought that I wasn’t going to do this, and was a little unhappy with myself after the first few, finally giving in and sharing the whole day.

It’s not that I want to stay hidden or to keep these spaces for myself, but all week I had yearned to unplug and escape social media. And here, with every chance to do just that, I pulled myself back in. It was disappointing, but it was also a chance to share my morning with friends. It’s often difficult to tell what I actually want.

The ranch road I was walking made for a feeling like I was walking in history. Not just geologic, which was evident all around, but a history not too long before. These rough roads, now thankfully barred to motorized vehicles, were run by trucks and jeeps following the Second World War.

The eponymous lakes – Ancient and Dusty – also date from this time. For decades, both coulees were completely filled with water for and from irrigation. They were, essentially, reservoirs, and the strandlines from the varying water levels can still be seen along the slopes inside the coulees. Maybe the wheel that I photographed during the first part of my hike is from that era.

It was then that Ancient Lake got its name, though the people who named it knew it wasn’t ancient at all. But it’s a good name, so it stuck. But hell, even the coulees themselves aren’t ancient. I think we might have learned a lot since then.

I had nearly made a circle, drawing close to the shelf overlooking the Columbia, to where I had scrambled down the talus, to where the ravens played in the morning sun. I had searched for a path or trail out of this lower section and back to the main trail to the trailhead, but could find nothing and was running out of energy to explore.

The hike wasn’t a difficult one. The miles weren’t endless, but neither was my energy. I saw the path I took leading in and readied myself to hike it out. The ravens were gone, now roosting or playing somewhere else. The balsamroot flowers were still following the sun. The rock buckwheat flowers, which had been closed this morning, were now opening, likely for the first time that spring. The path was still steep and in full light of the sun.

After stopping to photograph a few flowers, I decided to just carry my camera slung on my shoulder rather than in my pack. Maybe I thought that I had already lived the moment, so having a camera at the ready wouldn’t matter. Maybe I needed to shift some weight.

I finished off the Fomapan and switched back to the color Fuji Astia and stopped much more often to rest and photograph and sometimes to just rest without taking a single photo.

Partway up the grade, I found a cool spot where the sun’s rays had not yet reached. I slung off my pack and had a fine view up and down the canyon. To this point, I had passed two other hikers, a couple returning from a camp they made the night before along the river.

Sitting there now, an older couple passed me. The husband was recording something on his GoPro and I seemed to have messed up his shot by existing. Pleasantries were exchanged and they made some remark about me finding shade. They weren’t wrong. I let them struggle up the hill and out of sight before I regained my feet and followed.

Finally at the top and back on the main trail, I could see that the waterfall from the morning was gone. It, like the lakes, was part of irrigation. When the orchard above the coulees was watering, we’d have a waterfall. When they weren’t, the waterfall was dry.

When I got back to my car, the parking lot at the trailhead was packed with over 80 cars. It was staggering. In the morning, there had been just 15, and already I was worried that Potholes Coulee/Ancient Lakes/the Quincy Lakes Unit of the Columbia Basin Wildlife Area had blown up.

And don’t get me wrong, it has. There are many times more people here now than were here a decade ago. And I never know what to think about that.

On one hand, too many people will overrun the land, or at least spoil the experience. On the other, if people don’t visit these places, if they don’t fall in love with them, we may lose them.

Potholes Coulee isn’t really in any danger of being lost. It’s well-loved and well-protected by the state. In recent years, they’ve actually added to the acreage. The locals visit often, and it’s not far enough away to keep Seattleites from invading. But still, there’s something about solitude.

Following my hike, I drove out and up to the next level of the canyon complex, the top level, part of the larger Columbia Plateau. I parked and hiked along a cliff that overlooked both Dusty Lake and Ancient Lake Coulees.

Below me were the two long canyons, and beyond the slot where the Columbia River flowed. Below me, my day was hidden, tucked away behind distance swales and falling unseen to the river. Also below me were dozens of scattered tents. But they were dwarfed by the breadth of the coulees, and even though there were more than I had ever seen, I had to look close to see them.

This second ramble added three miles to my day, but resting above even the spine between the canyons, above the hundreds of hikers arriving in their now more than 80 cars, I found that solitude.

Through the entire day, I shot only five rolls (the last was something called Kodak Lumiere, a sort of cousin of Ektachome with a bit more saturation). I’m sure I could have photographed much more, but at some point, I have to live my life and hike my own hike. And fifty photos from just a single day is kind of a lot if you think back to the times before content and digital.

That balance we try to strike as photographers between living in the moment and photographing that moment is encompassed in the much larger breadth of the day. I struck some sort of balance that day. It wasn’t the most balanced balance, but I’m more than satisfied with the hike and the day as well.

As for the photos, like the hike, they are what they are. This was my day, this is how it felt. This is my photography.

Share this post