Last week I told you a story, I told you about my first hike of the season, I told you about solitude and how important a role it plays in where I travel, where I photograph. Last week I told you all about it, I told you almost everything. It was, however, a lie of omission.

“I scrambled up some natural steps,” I told you, “between sagebrush and giant boulders left stranded.” Before taking in the Columbia River still hundreds of feet below, I took out my phone, recorded a video, and posted it to Instagram.

I told you about walking the ranch road, which “made for a feeling like I was walking in history” without telling you that I took out my phone and recorded another video, posting it again to Instagram.

The same was true for the balsamroot flowers, as it was true for the walkway on the basalt cliff. The same was true for the bus, except I took two videos.

The ravens, however, I kept for myself. They were my solitude amongst the imagined solitude and a miraculous 5G connection.

I made some glancing reference to all of this. “All along the hike,” I confessed, “I had been taking quick videos with my phone and posting them as stories on Instagram. I thought that I wasn’t going to do this,” I told you, “and was a little unhappy with myself after the first few, finally giving in and sharing the whole day.”

This is maybe the only fully true thing I wrote. But even this is understated. Even this seems like some throwaway line, lip service paid to some vague concept of the rugged outdoors I claim to seek. Solitude doesn’t work like that. Solitude isn’t just isolation. Solitude isn’t a place. It’s not where you go to get away from it all. Solitude is expansive and expanding, it is terrifying and fleeting. Solitude is a life. It’s thousands of days, hundreds of years, centuries all wrapped up in that moment you realize you are alone, that there is nothing that will touch you.

It is not the canyons, the desert, the solo camping trips. It’s not the hours or road miles before you, after you. It’s not even being alone, it’s not even lonesomeness. It is something you carry inside of you. Something concealed, something necessarily and only yours. Solitude is you. It is the very essence of who we are. It is not family or friends or community, but our solitude affects all of those. When we ignore it or get lost within it, our solitude affects those we love. When we embrace it, love it, trust in it, trust in ourselves, then we can offer our true selves to our loved ones.

The walk I took last week was not solitude, and not just because I had a data connection or because I talked to a few people. It was not solitude because every chance I had at solitude was cast aside by an Instagram video. I wanted solitude, but more than that, I wanted to reach out, to tell my friends and the people of my community, “hey, look at what I’m doing right now!”

I wasn’t content to spend time with myself, to get to know who I was that day. That connection I sought is a connection I have almost constantly. I didn’t really want to share my day as much as I wanted to ignore myself. And while connection and community are essential to life, so is solitude, so is connecting and communing with yourself.

In that way, the time away was a failure. And I needed some redemption, I craved that isolation, that chance for solitude.

An Explanation

And so, this past weekend, I tried again. It wouldn’t be a hike this time, I’m still not sure I’m up for that. It would be a drive. But I think I owe you an explanation as to what that means.

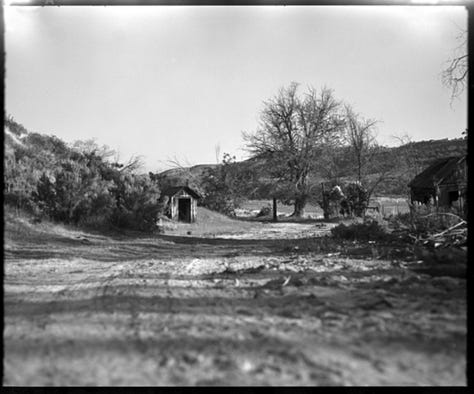

My drives are well-planned. I select lonesome dirt roads leading from stop to stop, photographing anything that catches my eye. I visit small towns, but even then, I keep to the side streets, the alleys, and secondary roads leading in and out. I’m not quite slinking or skulking, but I avoid the highways and asphalt as much as I can.

When I stop to photograph along the way, I take my time. In a way, it’s a meditation, a relationship is built or continued, as was the case last weekend.

I have driven almost every public road in Douglas County, Washington, from the highways to jeep roads that faintly trace their way across the sage and hills. This trip was a return, a rekindling. The locations I selected were mostly from memory, and I tried to approach them in new ways, both physically and mentally.

The landscape changes slowly out there, but it does change, and with photography, we have a record of that change. Our photography is the thought and the words of that conversation.

Cloudless

I was packed – two cameras, a few lenses, over a dozen rolls of film, and far more sheets than I would use. I had my tent, my sleeping bag, food, and a feeling that my solitude could come into play at least to some degree.

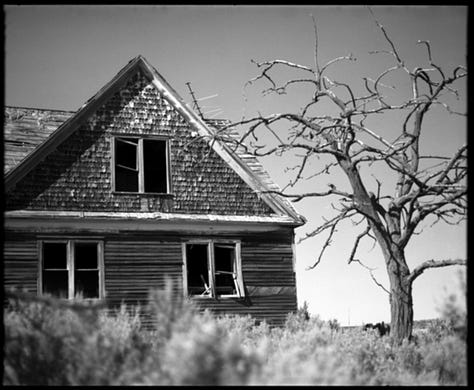

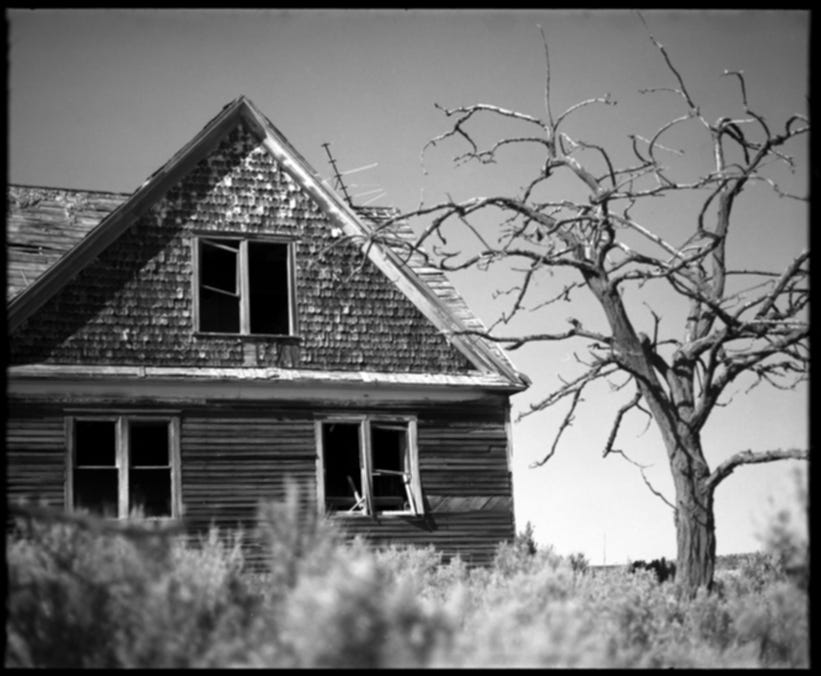

There was one large caveat, however. The skies would be cloudless. Normally, this would be enough for me to postpone a trip. Clouds are often essential to what I shoot. They frame my subjects, they are dark halos over once-loved homes, they are the heavens rendered reachable, touchable. Without clouds, there is nothing above. There is void. But there might also be solitude. And it was at this I decided to make the trip anyway.

I took my phone, of course. My offline maps were loaded on it, and it’s an essential tool for what I do. But I was going dark, not quite off-grid – I could still be reached (and reach out) if necessary.

My photography wanderings are quite an undertaking, with multiple trips from the house to the car, loading it with camera gear and packs. As I was lugging my 4x5 kit down the stairs to the car, I realized this. So much prep and effort are packed into a three day, two night excursion. It’s understandable why it’s so rare. But I don’t understand why I hardly leave the house otherwise.

Home

Apart from work, I am homebound. It used to be different. I used to go to the movies a few times a week. I used to photograph Seattle, taking on huge photography projects, which led me to explore the less-traveled parts of town. I once walked over five miles a day just wandering down various streets and paths through the city. But now, even with the beautiful spring, here I am inside.

To add to this, I used to publish a zine every month or so. I used to have a podcast with a world built around a growing community. I’d receive dozens of messages each day from listeners, friends, people asking questions, and others answering mine. I was online and connected about as much as I am now, but that connection seems lost or that it’s moved along.

I feel like I’ve been infected with a short attention span. Where once I was able to watch movies, even at home, with little care about what’s happening on my phone, I find myself wandering through uncountable YouTube videos and for no good reason.

Even on May the 4th, Star Wars Day. I wanted to watch something adjacent and picked Akira Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress and The Bogart & Bacall film The Big Sleep as interesting takes on A New Hope and Empire Strikes Back. But I didn’t. Instead, I just flipped through YouTube like I flipped through channels as a bored kid.

The movies and local photowalks take almost no planning or commitment at all, while my days-long trips take foresight and a level of preparedness that would keep most people from doing them. I don’t understand why I can hardly leave the house or focus unless it’s some big production. I don’t have answers here. It’s not that sort of thing.

Letters and Numbers

Most of the roads through Douglas County are laid out in a grid, each road exactly a mile away from the next, each road numbered or lettered accordingly. When I plan, I look for roads that break that pattern. They are placed where the land would not relent to an unnatural straight line. This was not even a compromise, we stood no chance, we gave in to the contours of the land.

There is a road which peels itself off from Road E Northwest called Road 13 Northwest. Because of the land, this road is mostly diagonal, curving along a sagebrush-covered ridge. Here, it is hardly more than a two-track.

In the spring, wildflowers grow in abundance along this road. Mostly it’s the balsamroot flowers, but also rock buckwheat, phlox, and buttercup. There are yellows and purples and whites mixed amongst the brown grasses and light sage.

In one particular spot, a large basalt boulder was planted, and with the cloudless blue skies and colorful ground, I stopped and spent an hour. Not a single car or truck passed by. It was me and my 4x5. I used strange and expired color film. This is duplication film, never meant to be exposed inside a camera. I knew it would draw out the colors, saturate the scene, bring every color to its most intense. It would look the way it felt.

As I walked the small prairie, placing my tripod among the flowers, I missed the clouds. I knew I would. The clouds add a dynamic to our static scenes in the same way wind might. I love to force long exposures, capturing the wind on my photos – the flowers swaying, the leaves a blur, the clouds smeared across the sky. And here there was nothing. Not a cloud above from one wide horizon to the other.

I missed them, but was resigned. It was what it was, and there was little I could do but capture this cloudless day.

Botheration

But to what end? It’s not that I suffer from impostor syndrome – the idea that someone will finally catch on to the truth that you have no idea what you’re doing and hold no qualifications at all to do it. I know where I stand as a photographer and am fine with whatever my abilities are.

My issue is that I can’t convince myself that anyone cares, and also, why should they? It’s not that I don’t want them to care, but I also understand why they don’t. “What I do isn’t for everybody,” I tell myself, which is really another way of saying that what I do doesn’t matter.

The evidence for this floated thoughtlessly through the air around me. The reason my books don’t sell like they used to, I’ve convinced myself, is because nobody cares enough to buy them. It’s got nothing to do with the photography community becoming more insular and cliqueish. It’s got nothing to do with algorithms and chance. My complete lack of self-promotion couldn’t be the reason. It’s the reality I’m living in now, and with each book I print fewer copies of, the more copies I have left over.

As I took my final photo of the boulder surrounded by a thousand flowers, I thought of this. I thought to myself, “Why bother?”

It hasn’t quite dug and wormed its way to the depths of “why bother photographing anything at all?” But I can’t say it hasn’t entered my thoughts. I photograph because I am in love with photography. It is selfish, it is for me. It is part of my meditation, my solitude.

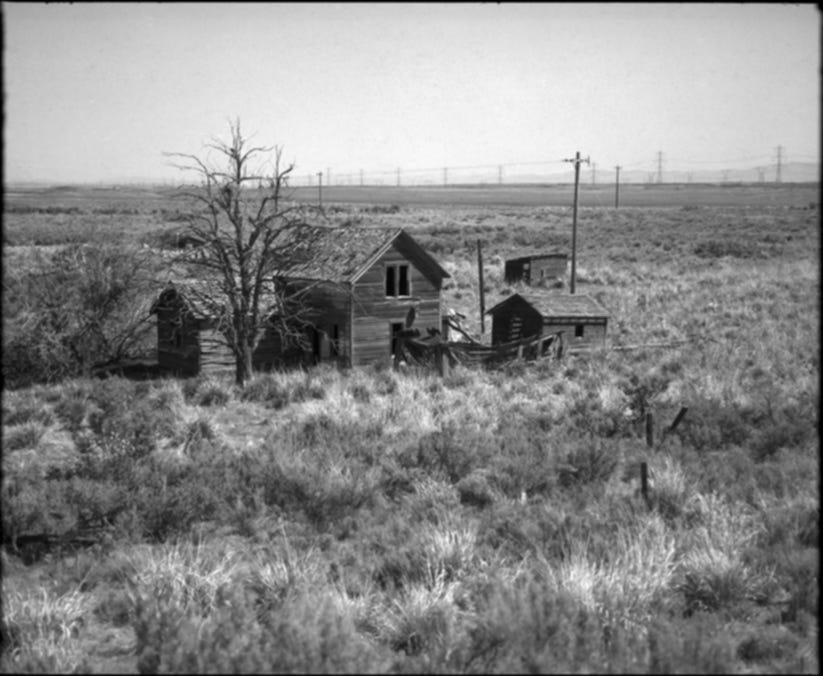

26 ¾

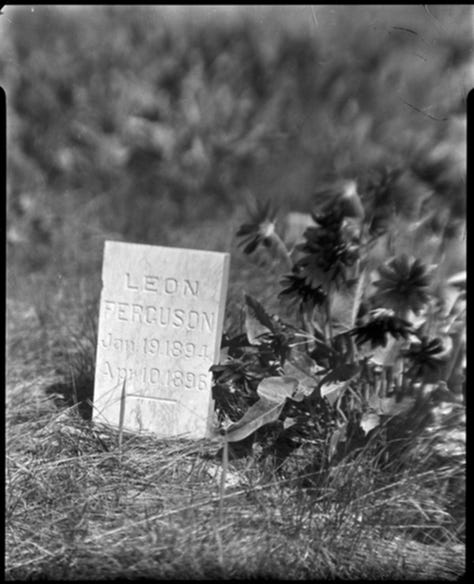

I drove a hundred dirt road miles that day, stopping every few to photograph a cemetery, an abandoned home, or some landscape. But at first, the pictures were hard to take, it was difficult to decide what was and wasn’t a composition. My concentration was returning, but was not yet returned.

I have kicked around several projects over the years that encompassed this ground. Most recently, I wanted to do something with Road 26¾ Northeast. It begins at Road Y Northeast and stretches diagonally to where Road Z Northeast would live if there were a Road Z. The lack of Road Z has more to do with the land than with any naming convention.

After it straightens out, it becomes Road 26 Northeast, crossing Strahl Canyon Road – one of the rare unlettered and much less straight roads. Continuing east, 26 becomes barely a trace before regaining breadth at Road C Rex. Rex is a suffix tacked on to any road that exists east of the mythical Road Z. When it flips back over to A, it is Road A Rex. I’ve never received an adequate answer to why “Rex” was employed.

In the evening of the first day, I found myself on Road 26¾ Northeast. With the sun lowering behind me, the golden light of evening cast its long shadows across the boulders strewn along the hillsides and the rows and rows of powerlines and pylons just to the south.

There are numerous and unnamed lakes skirting the edges of Road 26¾ Northeast. Even after it straightens and drops the “¾,” the lakes and ponds remain. I’ve waited hours here before, alone with the empty spaces. I have never seen another person on this road. This evening, however, I stopped here and there for a quick shot with the Mamiya RB67. There’s no need for a tripod, even if there were time. I felt in a small hurry and knew I would return the following morning, taking the road west to catch the early light. That is my golden hour. The evening is beautiful, to be sure. But the morning is a resurrection. It is all life and light anew.

In my hurry, I didn’t have time to notice the cloudless sky. I didn’t think of my books, my projects, and perhaps a new one forming itself. I didn’t remember Instagram, I couldn’t recall the last time I spoke to someone. I collected my few photographs and left.

That late evening, I set up camp in a small, little-used campground along Banks Lake, the man-made reservoir created when they erected Grand Coulee Dam. Someday, I would love to see it drained. I set up my tent, crawled into my sleeping bag, and shivered my way through the night. A coyote cried off in the distance, and then another, their distant calls and talking not so different from ours.

Morning

With the warm dawn, I returned to Road 26 and the cloudless sky. Not everything we want has to align for us to create. Perhaps it’s even better when things are askew. When we can conjure something artistic out of the chaos (or, in my case, the dreadful curse of a cloudless sky), that is where we can experience our true creativity.

Creativity, like solitude, is inside of us; we only have to learn how to draw it out, how to trust it, how to love it properly.

I stopped by a pond that I had driven by the evening before. Here, the pylons reflected themselves in the still water, uncontorted by ripples. I parked on the hill above and walked with my 4x5 and tripod along the road.

Sometimes I’ll do this – I’ll park some small distance away from where I want to shoot, just to approach it on foot, slowly, deliberately. I set up my shot, taking a handful of black & white and a few in color. I wasn’t sure which was best suited, and as usual, I’m still not.

Long ago, I fell in love with the often grotesque infusion of industry and technology among nature. Here, with the pylons and towers stretched and lined across a landscape randomly dotted with boulders and lakes, that strange perfection is on abundant display.

There is no cell service on most of Road 26 Northeast. Here and there, as you crest hills, and if the wind is right, you can receive the messages you missed when you were down below.

Sacred Communication

As I photographed the scene of parallel lines strung across the land, I thought how this was almost a metaphor for how we used to communicate. Here, all I had to do was walk up a hill to receive my messages. Before the internet, we communicated mostly by letter (a long-distance telephone call was prohibitively expensive, while a stamp cost only slightly more than a quarter). All I had to do was walk to the post office and pick up my mail.

I wrote and received a lot of letters back then. Each trip to the post office yielded several, and often zines as well. These were the punk rock days, and communication via the United States Postal Service was almost sacred.

Each letter was written in our solitude, and when we read the letters received, we looked into the solitude of others. It was personal and infrequent, even though we often wrote to each other a few times a week. There was no way to send a text message or email, no expected immediacy to our communication, to our relationships. And each letter received was tangible, real, it was permanent.

This sloppy metaphor falls apart with the slightest breeze. A walk up the hill to check my messages would mean someone would see that I received them, which would mean that I would have to respond immediately, thoughtlessly (so as not to appear thoughtless). And also, with the messages came a thousand distractions, a thousand things to pull me away from this solitude, this meditation.

With a letter, there was something worth savoring. There was something worth drawing in, reading it over and over. There was handwriting, there was the smell of the paper, the house it came from. Often, we’d send small surprises with the letters – stickers, bizarre Christian comic books, zines we found, mix tapes. Everything to say “I thought of you.”

Up that small hill, I had a cell phone connection, but I remembered back to when we could maintain our connections without a connection. Sometimes I brush all of this off as pointless nostalgia. But it’s not empty sentiment. I truly was happier then. It’s not that I am a Luddite or rage against social media, text messages, and assumed immediacy. I have fully adapted and will likely live the rest of my life with this.

But I appreciated communication more when it wasn’t so easy to communicate. I loved that connection more when there was no continuous connection. It all felt special because it all was special.

Go Back

As I walked back up the hill to my car and to a chance not taken to check my messages, I wondered if we could go back. If we could send letters and prints and zines. Not for the sake of nostalgia, but because it was actually and realistically better.

I wished for a way to share photos without the internet, without wading through ads and an absolute constant stream of information and media. Could we still divorce photography and art from content?

There is a midwestern writer named Sanora Babb who wrote a few novels and published short stories in the 1930s. I remember reading in the introduction to her novel The Lost Traveler that writers “like Jack Conroy, Miriedel Le Sueur, Babb, and other isolated midwesterners shared a virtual reading room together as youths in widely scattered towns and farms. Their interests merged—in literature, writing, and politics—despite their isolation. They knew one another, in most cases, only through letters.”

Could such a thing still be possible? Is it realistic? Practical? In a world where we value efficiency and constant turnover, I have my doubts. But what would it be like to share prints and zines and even long letters physically rather than digitally? How would that change us? Where would that take our relationships? How might that affect our photography?

Spencer P.O.

I kept these thoughts with me as I drove away from Road 26¾ Northeast. They followed me through a patchwork of public and private land, littered with No Trespassing signs, cleverly posted along tattered public roads in hopes of scaring away anyone wondering if they might illegally cross some imaginary line, all under this cloudless sky.

Knowing these lines well enough, I followed such a road west and then north, skirting a field of the first green stalks of wheat breaking the soil. Before me, as my car bottomed out on the center of what was now passing for a road, I saw Chester Butte, a small rise taller than any of the other small rises on the Columbia Plateau.

It was covered in wildflowers like splotches of yellow and purple paint splashed across the hills. With my RB67, I crisscrossed my way to the top. Returning once again to a cell phone signal I ignored. Below, the public and private land mixed as one, with young wheat fields and canola fields blending in with craggy basalt coulees and sage. In the distant west, I caught glimpses of Moses Coulee carved north and south across the huge plateau.

Over 100 years ago, the small town of Spencer grew inside this coulee. There was a hotel, a cafe, and a post office, which served as a singular point of connection for the area ranchers and farmers to the outside world. For them, a letter wasn’t just a quaint way to keep in touch, it was the only way to send or receive information and news about scattered family and the outside world.

Sanora Babb wrote about her love for mail in An Owl on Every Post, when she lived in 1920s Kansas, but life in Moses Coulee back then was not so different.

“As soon as the mailbags were dragged into the post office, people gathered and talked and waited—mostly waited without talking—for the postmaster and a helper to put up the mail. In this town and others to follow, it was I who went for the mail, one of the best pleasures.

“There was talk outside on the sidewalk, but in the post office, there was now almost complete silence as if everyone was listening to the significant whisper and slide of the letters and papers being sorted and placed in boxes and cubbyholes.”

Atop Chester Butte, I thought of Spencer, I thought of Sanora’s words, which I had read the night before. I remembered that sound, that “significant whisper and slide of the letters” as the post master of my small hometown sorted the mail – a town so small, we had no delivery to our doors, but had to visit the post office to pick up our mail. I remembered the sweet adhesive and paper smell of the lobby, how we greeted our neighbors, how we talked and gossiped. It happened daily, but it was an event, it was something we looked forward to.

Our post office was like this hill, Chester Butte, where I was standing. It was our connection. We had televisions and telephones, the radio and newspapers, but the post office was somehow more important, more official. The news and weather were for everyone. The mail we received was personal. Here was a place where we gathered and talked and went our separate ways in our solitude, holding letters filled with news from far-off friends and loved ones that meant nothing to anyone and everything to us.

I made a lot of zines when I was younger. Again, these were the punk rock days. I’d tape them up, put an address and stamp on them, and they’d be delivered across the county in only a few days. A couple of weeks later, a letter would be slid into my post office box, written by whoever received the zine (usually already a friend). They’d give me their thoughts and tell me about their week. Often, a zine would be sent with their letter, and the correspondence would continue back and forth for years.

I thought of this atop this butte and wondered where any of them were now; wondered if we might have kept in better touch if the internet hadn’t happened upon us. So much immediate connection killed the so much more meaningful connection.

The way down and away from Chester Butte brought me once again to the thoughts of solitude and letters and how we’ve lost both to the very way you’re reading this now. These words wouldn’t exist without the internet, but then maybe they wouldn’t have to.

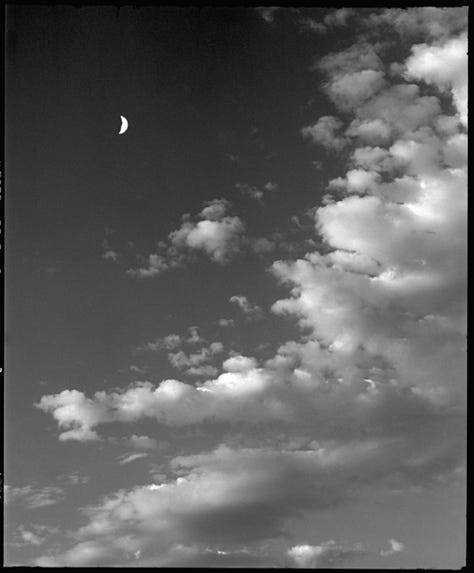

Clouds

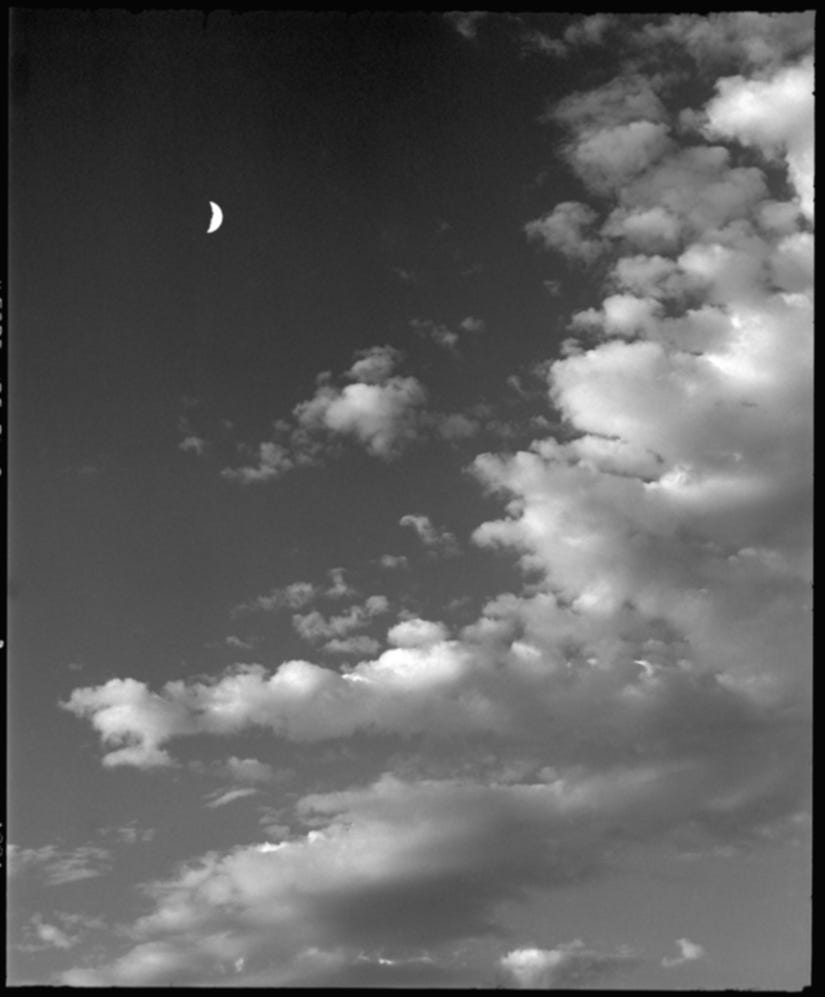

The rest of the day brought me through Moses Coulee, past what used to be Spencer, across the southern reaches of Douglas County. I shot sixteen or seventeen rolls of 120 and a couple of dozen sheets of 4x5. I camped near where I hiked on my last trip, and that evening I saw my first cloud.

With one frame left in the RB67, I took its photo in the coming evening air. The miles behind me unwound through my head as I watched the clouds move and gather and separate with the breeze.

For all those miles, all those scenes and photographs, the skies were clear, formless, cloudless. There was nothing above and all that existed was below, was near me, was part of me. But now the clouds had gathered, it was time to go home.

Share this post