[Before we start, I want to let you know about my new zine, Cloudless. It’s now available, and you can pick it up here.]

The narrow dirt road straddled the Idaho/Washington border with late spring wheat fields, their stalks nearly to my knees, growing on either side. I stopped the car on a hill and waited for the dust to settle so that I might see the scene behind me in my rearview mirror.

I stepped onto the road, grabbing my camera and checking to see again what I had loaded. The road ran through a small cut into the hill, with steep enbankments rising above on either side. I scrambled to the top of one and saw the green wheat undulating like waves on a vast and uneven ocean.

The hill I was on rolled its way to a small valley and other hills rising in the middle distance. An old barn stood in the valley, its wooden walls decaying and its tin roof patched, but intact. Light clouds dotted the sky.

I raised the camera, took the photo, and slid back down to the road. This entire encounter took maybe thirty seconds. I stumbled into a lovely composition, and the photo nearly took itself. I was back in the car and driving to the next picture.

Just how much thought I put into this photo, I couldn’t tell you. I know a good composition when I see one. I saw one and took the photo. It’s not that I didn’t think, it’s not that I just shot. I quickly scraped together whatever experience and foreknowledge I had, saw the photo before me, and took the picture.

Lomography

There is a film company called Lomography that markets its rebranded films to photographers who want a certain lo-fi look. It plays well on nostalgia, and they’ve managed to turn the memories of grandma’s photo albums into a thriving business.

On each roll of film they produce, they’ve printed their slogan: Don’t Think - Just Shoot! There is something mildly philosophical about this. I understand immediately what they want us to believe they’re saying. “Don’t overthink the photograph, go with your gut, shoot it!”

Of course, what they’re actually saying is “buy more film.” After all, they are a company whose priority is the bottom line. The more film we shoot, the more film we buy. And the more film we shoot without thinking, the more film we blow through like a mid-80s wedding photographer.

I can’t stress enough how bad this advice is. The advice is as bad as the faith of Lomography’s argument. It is only made worse by how obvious and brazen a cover it is.

And still, on this trip, I brought along a film Lomography called Potsdam. Before the rebranding, the film was made by German motion picture film manufacturer ORWO, which called it UN54. I used to buy it in bulk back in my 35mm days. The only way to acquire it now in medium format is to buy it as Potsdam from Lomography.

I love how this emulsion handles shadows, how inky dark it can be. There is a contrast to this film that you can ply with a yellow filter, or even red. I would shoot this film more, and might even use it regularly if not for Lomography’s lack of quality control. But more on that later.

Cows

I often find myself driving through range land, where cows and sometimes sheep roam free. An awareness of this is necessary when I’m driving, and caution is always in order. A few years back, while driving near the Missouri River in Montana, I was surrounded by cows with their young bulls. One of the bulls spooked and, rather than running away from my car, ran into the front quarter panel, putting a huge dent in it.

I stopped to see if he was okay - he was. And then I called my insurance company to explain that a cow had hit my car. “You hit a cow?” she asked. “No,” I replied, “other way around.”

Cows are usually skittish and fearful of us. It’s no wonder the hell we put them through. Taking their photo is something that almost never happens for me. The car already frightens them, and then when a human emerges from this metal cage, it’s basically the end times.

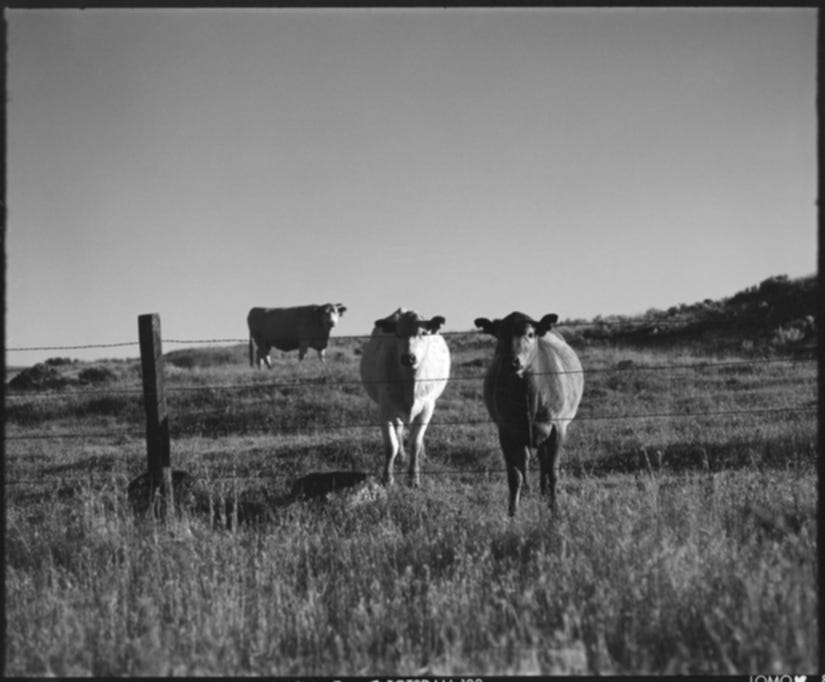

But along a Summer Road I’ve photographed before, I came across cows and heifers on both sides of the road. They were behind fences, and there were no young and frightened bulls to be seen.

The older cows were immediately uneasy, but the heifers, maybe a year old, were curious. Their eyes met mine, and they stood watching me. Another walked closer to get a better look.

I slowly went for my camera and began talking to them in a soft voice. I have no idea if this mattered, but it put me at ease. I walked from the road, over a small ditch, and into the grass where the barbed wire fence was strung, separating the cows from the road.

They stood, just looking, though I could see the clouds of hesitation and anxiety building behind their eyes. I lifted the camera and focused. This is usually as far as I’ll get with cows. At this point, they’re taking no chances and running away, often creating a mini-stampede.

This time, however, they just watched. They looked into the camera. There were three of them - two younger, one older. I was afraid that the loud click of the shutter and mirror slap of the Mamiya RB67 might scare them away, but even that hardly registered.

I took several photos of the trio and another of a mother and calf, who also cooperated, though with much more apprehension.

I had to work quickly. I had no idea how long my luck would hold, how long the cows would tolerate this strange event happening before them. I had to “just shoot,” worried that I might miss the opportunity. But I never stopped thinking, I never ceased calculating the odds of getting just one more photo.

In the end, that wouldn’t have mattered to Lomography (whose film, Potsdam, I was shooting). I quickly finished the roll and loaded another. They don’t really care if you think or not, they just want you to shoot more. And I did. Then, with the next roll of Potsdam ready to go, I returned to the car, grateful that the cows were brave girls. The boys could certainly learn some lessons.

The Worst Question Ever

Back in the days of the previous podcast, I interviewed dozens of photographers. Through all of that, there was one question I never asked, one question that nearly every other film photography podcast asked first: “Why do you choose to shoot film?”

It’s not that it’s necessarily a bad question. It’s just that nearly every film photographer answers it the same way - some variation of: “I shoot film because it makes me slow down.”

This answer, like the photographers answering, comes at the question from the aspect of a former digital photographer who thoughtlessly shot everything as quickly as they could.

It’s understandable; that’s how digital photography was marketed. With film, you had 36 exposures at most before you had to change rolls. With digital, you’ve got hundreds.

However, these are two different issues: one of speed and one of capacity. They’re not actually related at all.

The push for faster photo-taking wasn’t invented with digital cameras. All through the 70s and 80s, film camera manufacturers pushed how quick and easy their new cameras were. From the motorized backs for medium format to the point & shoot 35mms, how quickly we could blow through frames was a huge selling point.

Wheat

There are small dirt roads that are rarely driven by anyone but farmers to and from their tractors parked on the edge of their fields. But I drive them. There are seldom homes along them, no businesses, rarely even barns. But here, the roads rise and fall with the land. Only slightly graded (maybe once in the springtime), these Summer Roads offer us the closest feel we’ve got to the roads of the territorial days, the days before the car.

As I bounced along one, driving west with the morning sun at my back, I was again between wheat fields. The road was straight and level, though a small ridge rose beyond. In the middle of the road, as if planted on purpose, grew a small and struggling stalk of wheat. Its leaves wrinkled unshaded under the sun, yet still several spikes of grains grew in seeming defiance.

It was not purposely planted here. It likely fell accidentally from a seeder and somehow managed to take root. Standing alone in the center of the road, the stalk of the plant was missed by the tires of tractors and trucks over the months it had been growing. I could have driven over it, not harming it in the slightest.

Instead, I stopped. I sat there looking at the stalk, wondering how I could photograph it. I don’t know how long I considered the scene. Was it even worth it? Before very long, I grabbed my camera from the back seat and walked up to the plant. I’d probably be the only car on this road all day. I had time.

Looking over this stunted stalk of wheat, I consciously mulled the decisions between color and black & white, between a wide aperture and narrow. Did I feel it should be horizontal or vertical? I know I wished for a lens wider than the 90mm. It wouldn’t be the first nor last time that thought crossed my mind.

The light was perfect. The sun was high enough so that I might not cast a shadow onto the plant, but low enough to bring definition and texture to the leaves and seeds. I knew I had time, so I took it.

Crouching, knees now in the dirt of the road, I took my first shot - a simple black & white picture with the wheat in focus. I decided to open the aperture and held myself steady to not miss focus. I knew the fields on either side of the road would fall to a mostly ill-defined blur, but the road and the tread from the trucks driving through before me would show. The story of just how this little plant was surviving would be told.

Following the shot, I returned to the car for the color film loaded into a different holder.

I walked back to my previous spot, framing it over again, but closing the aperture slightly to allow the wheat fields to come into their own. I wanted them to echo this little plant. I tried another from the same position, this time focusing at infinity. This was pointless, and I think I knew it at the time. The small stalk of wheat blurs and blends into the smeared foreground as the ridge beyond takes sharp focus. While it’s halfway interesting to view the scene as we’d see it with our eyes, that isn’t really the point of my photography. I want to show you what we don’t automatically see.

These three shots took five or ten minutes. It wasn’t overlong, it wasn’t toilsome, but I took my time. I did the work. I gave the scene the thought it deserved.

Sometimes scenes require this. They demand our attention, they deserve our thoughtfulness. Even when the composition is obvious, even when we know the results, we pause to consider, to experience. This isn’t unique to film photography or even photography in general. Here, I’m pausing to grow myself into the scene. To learn the landscape, the subject. A camera is secondary. Film is nearly an afterthought.

When we tell ourselves that we shoot film because it slows us down, I think this is what we mean. At least, this is what we want to mean. It’s not slowing down for the sake of slowing. We slow down to match the pace of nature, to return to our natural rhythm. We are winded from our lives of constant movement, communication, and information. We are catching our breath.

We slow down, but it’s not for rest.

The Bridge

Rest is not a luxury I dabble in when on a photography trip. Typically, I drive until I see something, stop the car, hop out, grab the camera, get the shot, and climb back in the car to be on my way. This becomes a flow, a repetition echoed through the day.

The cycle is only broken when I switch to large format. Here, I use a 4x5 field camera. It’s actually lighter than the Mamiya RB67, though with the entire kit, including multiple lenses and a tripod, it’s a 25-pound boat anchor to be lugged from the car to hopefully some scene close by. I hike with the same camera, though the kit that I carry for that is drastically pared down.

I had photographed all morning, rising from my tent with the sun, and spending uninterrupted hours on the road, grabbing photos where I could. I shot four rolls by the time I arrived at my last stop.

The road to the concrete bridge is one and a half miles of dirt, rocks, ruts, and washouts. A high clearance vehicle and dry weather are required. I picked my way through the sharp points of basalt littering the road and worked slowly to the bridge.

This 1915 concrete arch bridge spans a fast-flowing creek over a small series of waterfalls. I have been here half a dozen times before, and try to return at least once a year.

I have photographed this bridge and the surrounding land extensively, and while I have no problems with shooting the same images again and again over the years, I wanted a different take this time around.

Hesitatingly, I crossed the old bridge, its floor now covered in the same dirt as the road. The same grasses and plants have grown on this bridge for decades. The road itself used to continue to a town that no longer exists and then to a ranch that is now a wildlife preserve. I parked just across it.

The sun was hitting the bridge’s north side best, and I scrambled with my kit over a barbed wire fence. The land all around this scene is public, most of it owned by the state, and the rest by the federal government.

The creek cuts its way through basalt bedrock, following a large canyon likely carved out during the ice age. Because of this, the rocks are sharp and brittle. Though this isn’t a tourist destination and is mainly used by locals, it sees enough traffic for there to be a web of unofficial paths and trails throughout.

With my eye on the short waterfalls, I walked a skinny path along a cliff, lowering myself down to the water’s edge. Here, I framed a number of shots, focusing upon the water, on the grasses, on the bridge. I shot both color and black & white, spending about an hour and a half on the endeavor.

This was not like photographing the little wheat stalk or the cows, it was fully different than the quick picture of the barn among the hills and fields. This was, to put it in some vague cliche, a meditation. I took six or seven photos over those 90 minutes, and yet there was no rest.

I moved from one rock to the next, tearing down and setting up my camera each time. I scrambled over boulders, slipped my foot into the water, climbed my way back up the cliff to my car for more film, and back again to shoot it.

My heart raced not just from the excitement, but because it was a true workout. I felt amazing. I felt better than I had all day. Here, I was in my element, in a location I knew well and loved even more. I was with a camera that is as much a part of me as any camera can be. I felt at home. Here, I finally felt like a photographer.

Not that I don’t feel this way when I’m taking quick shots, hopping in and out of the car, but it’s a different sort of thing.

I’m not just racing, of course. I’m not just a scattered mess of an artist, grabbing a lens and dark cloth through the chaos of my rattled mind. If anything, it’s the opposite. I’m never a technical photographer, but during this hour, I was living out what every photographer wants: to think and to shoot.

Lomography Again

Where Lomography’s stated idea falls apart is with failure. What if you didn’t think and you just shot, and none of your photos turned out as you hoped? Lomography has a plan for this as well – any blemish, any mistake, and more importantly, any emulsion or quality control issues on their end, are all part of the unknowable mystery and happenstance that is film photography.

It should come as no surprise that Lomography’s quality control is basically nonexistent. Remember the rolls of Potsdam I used with the cows? When I developed them the next day, I saw that there were white specks all over the emulsion. They rendered as black dots much larger than grain when scanned. This is apparently a common thing for them. They know this and have done no recalls and given no warnings. Instead, we’re told to “embrace and enjoy” the randomness of film photography.

The same rolls, with “Don’t Think, Just Shoot” printed on the backing paper, came out of the camera as loosely wound “fat rolls,” allowing light to leak onto the already-exposed film. This, too, is a known problem, and Lomography doesn’t even bother to acknowledge it. Don’t think about it. Just shoot it and marvel at the randomness of film. It’s a racket.

End

After the hour and a half had passed, it was time to leave. When I arrived, I was alone, but after I took a few photos, a truck pulled up, and then another. This is a fairly popular fishing spot among the few who know about it.

On the way in, I saw a composition that I wanted to shoot on the way out. Here, the road is a two-track and angles off between a fenceline and basalt formation.

I had a few frames left on the Mamiya, more Potsdam. I framed up the shot and took it with me. It was one of the few shots that came out on this incredibly flawed roll.

A number of things went wrong with my film from this trip. Some of them were Lomography’s fault, to be sure. But some were my own. In one shot, looking under the bridge and across some of the falls, I missed focus. In another, my composition was so bad that I couldn’t imagine what happened. And with the black & white sheets, my developer was dying, and they came out thin and grossly underdeveloped.

While most of my shots came out that day, the ones that didn’t are lost. This is sad, of course, but I remember taking these shots. I remember how the day felt, the joy that had come over me while photographing. I remember it all simply because I was thinking. I wasn’t just shooting. All of those photos are still with me, even the ones that didn’t turn out.

It is not film photography that allows us to slow down. It is our discipline, our dedication to our art, our love of the subject that makes slowing down worth it. Slowing down isn’t about shooting less; it’s about thinking, about experiencing the scene; it’s about living it.

Share this post