Did you ever have someone get really intense with you over something you said? They were insistent, and even their arguments seemed a bit more involved than just boring semantics. Maybe they were even angry. And it’s someone whose opinion you valued, so immediately, you took a step back and gave a long think to whatever you said and how you said it. Then, after quite a bit of soul-searching introspection, you concluded that you were still right and what the hell was that all about?

One time I was casually talking to a fellow film photographer about how much time we all spend on film photography - “it’s our hobby,” I said, “it’s what we do.” They were really unimpressed with this. I wasn’t trying to be deep or even thought-out, but they took offense.

“Photography is NOT just a hobby,” they said, using the word “just” to fully and completely separate what they did for fun from what other people do for fun. “Photography is everything! It’s our artistic outlet, our means of communicating our emotions, it’s how we see the entire world!”

And that’s all true. But this photographer, like me, was not a professional. They spent far more money on photography than they saw in any returns from print sales, etc. We were pretty much on the same level of photographic intensity. It was indeed our lives, it’s what we thought of when we woke up and what we dreamed about when asleep. Every second of our day was consumed by photography.

At that point, I was more than happy with thinking of photography as my hobby, and myself as an amateur photographer. It’s a thing I did in my free time, and I didn’t get paid (in the sense that if this were a business, I’d have been bankrupt years ago). And this argumentative photographer was there too.

This conversation took me aback. Did I misunderstand what a hobby was? Was I not arting well enough? Was my photography lacking or inferior because I was fine with it being a hobby?

What is a Hobby?

At first, my suspicion was that maybe we were using two drastically different definitions of “hobby.” Wasn’t a hobby just a fun thing you did in your free time because you enjoyed it?

After collecting a few opinions on the matter, I hit the dictionaries and discovered, yes, that’s basically the definition we’ve all agreed upon in the English speaking world.

The entire idea of having a hobby is something that didn’t come about until fairly recently in Western history. It seems that the concept didn’t even invent itself until the 1500s when some wealthy people suddenly found themselves with nothing to do and they filled this free time with stuff that seemed like work (and actually was work to poorer people – like woodworking, needlepoint, and baking), but was actually something they did for pleasure.

The word hobby comes from the “hobby horse,” – a stick with a fake horse head on it. For some reason, possibly involving Tristam Shandy, that phrase was expanded to mean leisurely pastime. Eventually, the “horse” was dropped and “hobby” remained.

At first it was seen as a privilege to have a hobby. But by the 1600s, “hobby” had taken on a negative connotation. Maybe this was when the phrase muttered by every shitty boss everywhere came into being: “if you can lean, you can clean.” It is almost certainly tied to the Protestant work ethic. Hobbies were seen as play, and play was something for children. Western Civilization has been in decline since then. (I’m joking, of course, it was already well on its way.)

We have much more free time today than we did in the 1600s. However, we are also living through a period where free time is valued less and less, especially in the United States.

For me, photography is a hobby. It’s probably a hobby for you too, and that’s okay. I also have other hobbies. Obviously, etymology is one of them. So are music and movies. I recently got a fountain pen and I suppose I could make that a hobby if I wanted to (I probably don’t, and that’s okay too). Writing is probably second to photography and scratches many of the same itches.

Is Collecting Cameras a Hobby? Is it Photography?

Caught up in all of this is the strange fact that film photography actually encompasses two completely different hobbies. We have photographers and camera collectors. This is muddied even farther since the Venn diagram depicting the crossover is nearly a circle. Most film photographers have a collection of cameras, and most camera collectors are also photographers.

Some of the desire to draw a line between photography and hobbies comes from this. In some ways, I get it. I really hate gear talk. When photographers start talking lenses, I basically die inside. I just can’t do it. I just don’t care.

It’s not that I think it’s beneath me or not artistic enough, it just doesn’t interest me in the same way that knitters talking about different gauges of needles doesn’t interest me. That’s not my hobby.

I mean, I have a bunch of cameras like most other film photographers these days, but I don’t care much about them (and yes, this is a whole other thing I need to talk about someday). They’re fun to look at, and I’m basically fine with them being there, but I’m not a gear person. When someone asks me which lens I’m using, I have to look it up. I just don’t care enough to remember.

But I guess you could still call me a camera collector, or at least, a guy with a camera collection.

I’m the perfect candidate to look down on those photographers whose focus is gear rather than art. And I admit, it’s really ingrained in us to feel this way. It’s difficult not to. But it’s also shitty, and it’s important that we get over ourselves. Let people find their joy just as they let us find ours. And who’s to say our joy is more joyful, more pure?

Photography isn’t JUST a Hobby!

When someone says “photography isn’t just a hobby,” they’re actually admitting the 17th century Protestant work ethic idea that hobbies are childish, that hobbies aren’t important is true. They’re implying what they’re doing is art and is endlessly more important.

Calling your artistic pursuit a hobby doesn’t diminish what you love; instead, it recognizes that the love other people have for their pursuits is just as worthy and wonderful as yours. Calling it a hobby doesn’t lessen your skills and expertise. It doesn’t make you less of an artist. It’s just a good way to remind yourself that you’re doing this for the joy of it.

The problem with saying “photography is just a hobby” is that we’re also conceding that it is a hobby, but it’s also much more. And it is! Two things can be true! Most hobbies are more than just one thing. Most hobbies involve something that sets them apart from other hobbies. There’s a lot in photography that is unique to photography, but it’s not more unique than the specifics of literally any other hobby.

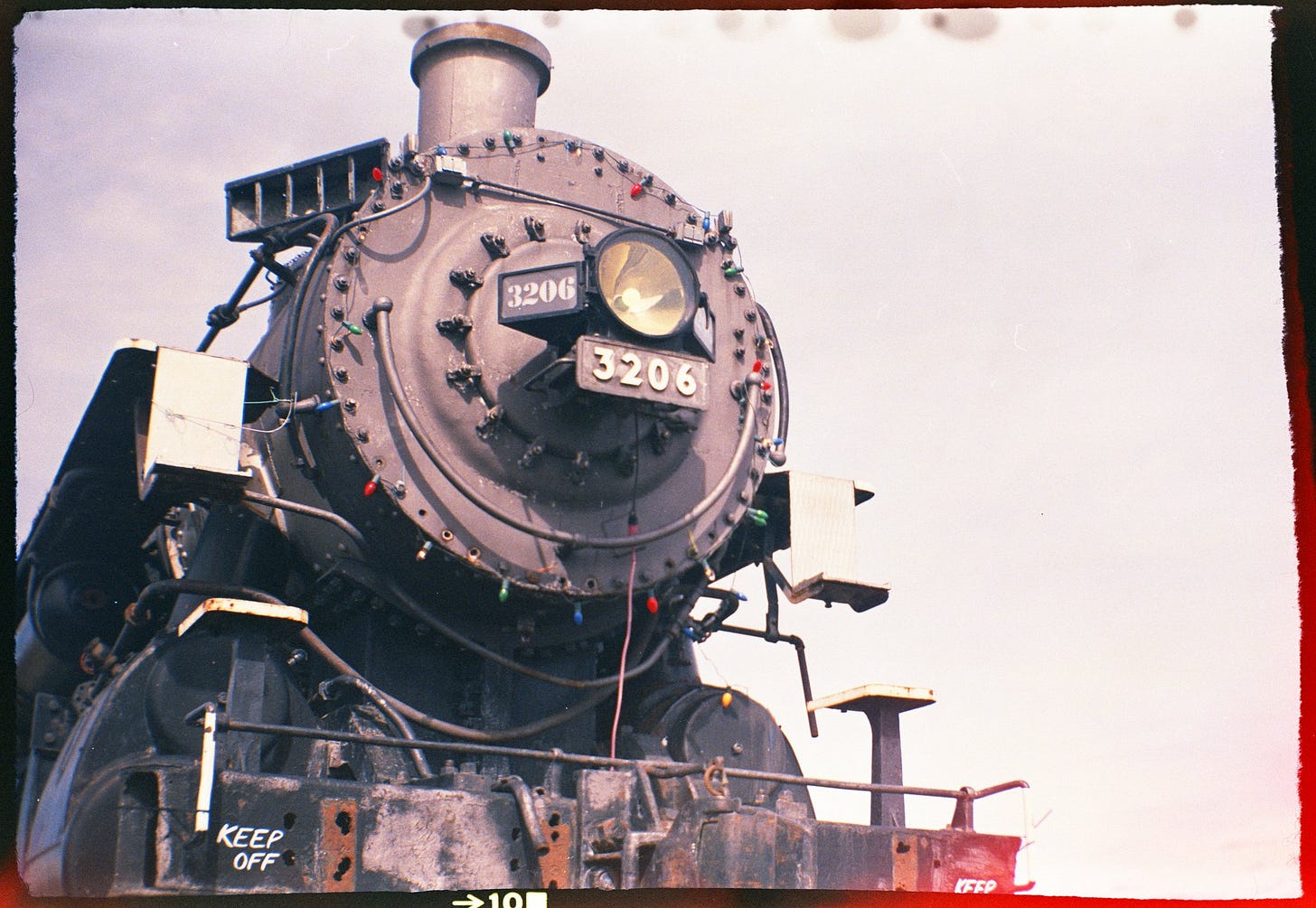

For me, the go-to example of a hobby is model railroading. It’s nice, pretty much everyone agrees that it’s a hobby, even model railroaders (is this because they’re not pretentious?). Model railroading involves a crazy amount of artistry, physics, research, skill, and free time. There are people even more into model railroading than we are into photography, I promise you. Pretty well anyone would agree that a good model railroad layout is a work of art, and yet they’re never counted amongst other artists. They sculpt, yet aren’t seen as sculptors. They paint, yet nobody calls them painters. They’re often pretty good photographers, too. But that’s not what they lead with. They are hobbyists and seem to understand the actual value of that word.

Meanwhile, we’re over here insisting that “photography isn’t just a hobby” because we can frame a picture and push a button. Maybe we need to recalibrate our enthusiasm.

The Way Out of Hobbies is Dumb

Film photography came back into prominence during a strange intersection of nostalgia and recession. It came about when vinyl records started making a comeback (for some, anyway – I never stopped). Things were turning very digital very quickly, and we longed for the analog.

Digital photography had completely usurped film photography, and nobody but the extreme purists and hobbyists continued to use film. Camera companies had stopped making new cameras, most emulsions were discontinued, Ebay and garage sales were stocked high with grandpa’s old gear.

This allowed for a very low threshold of entry for new and returning photographers. In many ways, this was equalizing. Suddenly, you didn’t have to be a professional wedding photographer to afford a Mamiya RB67 (the greatest medium format camera ever made) and a few rolls of (likely expired) slide film.

Soon, an entirely new community grew from where there was none. The old gatekeepers in their photography clubs were either ignored or ousted, as thousands of new photographers entered the hobby.

Unfortunately, this happened during the rise of hustle culture, a form of workaholism where pretty much every waking minute is somehow commodified. Often, it was done out of necessity, but like with anything, most people took it too far.

When it came to photography, selling prints, zines, and books had always been a thing. With the introduction of hustle culture, all of those were amped up, and things like seminars, tutorials, and even collaborations ended up seeming more scammy than useful.

This led to a very straight and dark line between consumers and producers, separating film photographers from those who do it as a hobby and those who were serious enough to charge money for doing it as a hobby.

We like to say that this kind of thing democratizes art. We like to think that since we don’t have to rely upon publishers and galleries like photographers used to, there are no longer gates to gatekeep.

This is a fairly dumb dividing line, though. What often keeps someone from making zines or prints is simply the upfront costs or the know-how, or even the desire to do one. It’s really no great achievement to select 30 or 40 photos, put them in order, and send it off to a print shop so they can make some copies for you. Being willing or able to do that doesn’t make photography your career and certainly doesn’t make you a better photographer.

The commodification of photography and of art in general can kill a sense of community. What art doesn’t need to thrive is a ‘us vs. them’ mentality. Artists shouldn’t have fans and followers. We should have supporters, yes. But we also should be counted among the many supporters of other artists.

The only way out of a hobby, apart from giving it up, is to turn it into a job, and for so many of us, that’s exactly what we did. Factoring in the film, the cameras, the travel time, the printing, almost none of us broke even. If photography were our job, we’d be unemployed.

That we can’t just do photography without feeling the need to make a buck or two on it doesn’t lift us out of photography being our hobby.

We Really Can Just Enjoy Photography

When we expect money in return for doing art, we eventually come to the conclusion that we will only be artistic if we can make a buck off of it. This isn’t unique to photography or any art, really. But it doesn’t tend to happen within most other hobbies.

Model railroaders, movie nerds, and Civil War reenactors don’t usually try to make money off of what they’re doing for fun. After all, it’s for fun, the very meaning of which is devoid of money. Why should photography be different?

Nobody has ever gotten into film photography because they had to. Nobody is forced to be here. We, all of us, want to do what we’re doing. We enjoy it. We love it. That alone should be enough to keep us going.

Imagine you are an artistic person who has found out that film photography is the specific way you want to express yourself. Not only that, but you also have the privilege of free time and the ability to make the art you want to make. You have answered this calling, fallen in love all over again, and end up thinking “it’s just not worth it to me unless I can make a little on the side.”

Imagine love and fulfilment not being enough. And then imagine thinking money will somehow make it better.

But also, I do get it. Film photography, like most hobbies, isn’t cheap. Film, like artificial trees and buildings to set up next to tiny railroad tracks, isn’t cheap. A camera, like a replica 1861 Springfield rifle, is kind of pricy. But in the end, it’s our hobby – whether or not I’ve convinced you it is.

The Moderation of Commodification

This is not to say that any and every exchange of money within the film photography community is somehow bad. That’s a ridiculous notion. We live in a capitalistic society, and that’s where we’re doing our art. Part of our creativity and artistry is in making prints or zines/books, and there’s no reason not to do that.

But then, that isn’t selling, that’s making, creating. We should create. We should make zines and books and help others by teaching them how to do it, too. And we shouldn’t charge for this knowledge. Not everything we do has to be commodified.

More importantly, we, as artists and creators, should also be supporters, especially of those just starting out.

I’m tempted to say that we flat out shouldn’t support celebrity photographers. They’re more than fine without us. But we shouldn’t support them if it means that our support for smaller and beginning photographers is affected.

Most importantly, we should be supporting the photographers closest to us. They could be within our local photography scene or good friends we’ve met online. Support those you have a personal relationship with first. Doing this fosters a stronger community, better friendships, it encourages those who might not have made zines to finally make one. It encourages people to join the hobby and helps those who are new to it go deeper into exploring their own art.

Be a Professional?

I am not a professional photographer. I’ve made and sold a bunch of zines and books, and when all is said and done, there’s no way I’ve come close to breaking even. But then, that was never the point. The point was that I could do these things, so I did them.

I have a regular job. I’m a screen printer. I have hours when I need to be there, I have a boss, and a paycheck. It’s a fine job, as far as jobs go. I’ve talked about it before, it’s nothing glamorous or artistic. It’s simply industrial printing. It’s a job that when I clock out, I don’t have to think or worry about it.

This isn’t some luxury that I’ve stumbled upon after decades of menial labor. In that respect, my job now is no different from the convenience store jobs I had in my early 20s. Once I was out the door, there was nothing you could do to make me think about work. And while I don’t hate my current job (and I absolutely hated working at a convenience store), both jobs gave me the luxury of leaving them at work.

Hustle culture gives you no such freedom. Unless you’re incredibly disciplined, working from home doesn’t either (are you working from home or living at work?). Being a professional artist usually requires you to employ your craft according to the wishes of your boss or client. It is exceedingly and mind-numbingly rare to be a professional independent artist.

I choose to be more than happy working a job that gives me the time to be a photographer (after work, weekends, holidays). And when someone asks me what I do, I tell them that I am a photographer. Because I am. Photography is my hobby, it’s not how I make my living, but what kind of life would I have without it?

Share this post