“You don’t take a photograph,” a young Ansel Adams might have said, “you make it.”

This is probably Adams’s most famous quote. And, it’s usually just something rattled off by your photography professor because it sounds deep and you gave them a bunch of money, and they have to say something at least a little profound-ish. And you were young and impressionable. You’d buy anything.

It’s used by a thousand semi-professional photographers trying to convince their potential clients that they’re doing something different, something more thoughtful.

But was Adams really trying to be profound or obtusely philosophical? Was his meaning truly the chasm of profundity we seem to believe it was? Or is this quote just photography’s “Not all who wander are lost”?

Ansel Adams thought that the act of photographing something should be a process, something well-considered, crafted. And it’s hard to disagree with that.

And yet, it always seems a bit cringe when I hear “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.” This could be my own hang-up, assuming that the person saying or writing it was being precious and pious. It sounds pompous and inflated with self-importance. This is because it often is.

Let me get this out of the way right up front. This is a pet peeve of mine. And since it’s a pet peeve, it means that I don’t have to care about your rational opinion of this because I fully understand that my opinion may not be rational. More importantly, I’d rather scan the curliest 35mm negatives than argue with someone about this. And no, you don’t have to listen to me and my dumb opinion, but here you are.

Etymology for Fun and Profit!

When we say “I am making a picture,” what we’re really attempting to say is that we have given this subject, this scene, or whatever we’re photographing some thought. We’re not just taking a throw-away snapshot. I don’t think that’s how Adams meant it, but we’ll get to that soon enough.

First, I want to dig into the words “take” and “make.” They rhyme, and that’s a big clue to solving this mystery of why some of us say that we “make” a photograph. And we’ll get to that later too.

One of my other pet peeves is writers who begin an essay, “the dictionary defines” whatever they’re talking about. It’s lazy, it’s poor form, and I know attacking it is an easy target, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be a target.

This, however, is different. We’re talking about two words that are, in the case of photography, almost interchangeable. Regardless of which one we use, we are exposing some chunk of photosensitive material to light. Both words describe the same action.

Both words, however, are very different, with wildly contrasting connotations. When we “take a picture,” it’s quick and thoughtless, but when we “make a picture,” it’s full of intention and purpose.

Historically, the words “take” and “make” are roughly the same age. “Take” comes from early Scandinavian, and we got “make” from one of the old Germanic languages. Both were welcomed into Old English a long time ago.

The definition of “take” is pretty straightforward. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “take” means “To seize, grasp, or capture something.” The original definition generally refers to capturing a town or vessel during wartime. But all of our basic definitions for “take” are drawn from this idea.

The definition for “make” is “to bring into existence by construction or elaboration.” It goes on: “To produce (a material thing) by combination of parts […] to construct, assemble, frame, fashion.” “Make” is about production, about the material produced. It’s the end result of whatever we’re doing.

Even now, we can see how “take” and “make” both have their parts in what we do. We “take” or capture a picture. We “make” or produce a material print.

Taketh a Likeness

But let’s go a little farther. Why did we ever say “take a picture”?

While it’s impossible to know who coined the term, it was first used in relation to imagery in the early 1500s. This was 300 years before the invention of photography. In the letters of Sir Thomas Cromwell, he mentions that someone would visit and “see his daughter and also take her picture.”

In this case, “take” meant “to paint” a portrait. Throughout the following centuries, we see this usage again and again.

Francis Meres complained in 1597 about someone “With such trimming and setting, and smoothing and correcting, as if ye meant immediately to have your pictures taken.”

Oliver Goldsmith wrote of a “limner, who travelled the country, and took likenesses for fifteen shillings a head” in 1767. [Side note: the word “likeness” meaning an image or painting, dates back to well over 1000 years.] [Also, a limner was someone who illustrated a manuscript.]

When photography came around, they just continued using the same word: take.

In an 1839 article about Louis Daguerre (one of the inventors of photography), an author wrote about his daguerriotypes, “Some of his last works have the force of Rembrandt's etchings. He has taken them in all weathers—I may say at all hours.”

The same word, “take,” was also used in early cinematography. “The biograph people came down from New York and took moving pictures of the ten-seater [bicycle],” wrote the Denver Evening Post in 1897.

To be fair, “make” did show up from time to time when talking about paintings, but it does seem to have been pretty rare, and always in the past tense, often in the distant or ancient past.

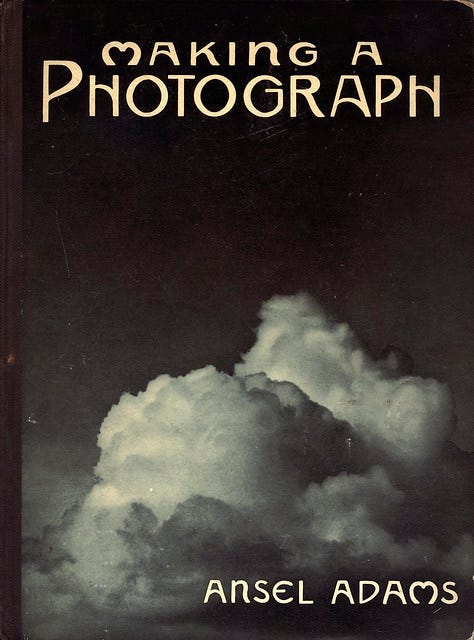

What we don’t see, however, is any reference to “making a photograph” prior to Ansel Adams in 1935. This is because, I believe, it was Ansel Adams who started this in his 1935 book Making a Photograph. It was Adams who redefined the word “make,” and all joking aside, that’s commendable.

But I don’t think he was using the word as we use it today, I think we’ve redefined it even further, twisting it and his quote to suit our own ideas.

Language is constantly changing. When I was growing up, “out of pocket” meant hat you had to pay a bunch of money because your shitty insurance wouldn’t cover something they said they would. Now it means ridiculous or crazy, though in retrospect, I see the connection.

There are two types of people when it comes to definitions and word usage: prescriptivists and descriptivists. Prescriptivists want words and meanings to remain as unchanged as possible. They want unchanging grammar, standardized usage, and regular spelling. Descriptivists look at how language is actually used rather than how it’s “supposed” to be used.

Normally, I am more of a descriptivist. I understand the need for standarization when it comes to writing, but languages are fluid and constantly changing. I love looking back through etymologies and seeing how usage and definitions have changed over the years and centuries.

But not here. Again, this is a pet peeve. I won’t be budging. With the take vs. make argument, I’m a prescriptivist. It’s take. Always has been.

However, the descriptivist part of me finds it a little interesting to see how the usage of “make a photograph” has slipped since Adams said it in 1935.

The Original Quote

But there’s something more to this. We’ve taken a look at the quote (“You don’t take a photograph, you make one”), but I haven’t told you the whole quote, the full context.

Are you ready? Because I don’t think you are.

“The unique quality in photography is a combination of rigidity, based on the pure physical, scientific facts of life, and the possibility of controlling that rigidity. You don't take a photograph, you make it. Expression is the strongest way of seeing.”

This appeared in a 1979 issue of Time Magazine. The quote is not sourced, but I believe it comes from his 1935 book, Making a Photograph. Ansel Adams was a wonderful photographer, but his writing leaves much to be desired.

I spent hours upon hours trying to source this quote to no avail. What I also found is that the quote we know, the “You don’t take a photograph, you make it,” doesn’t show up on its own until after his death.

For how often it’s quoted, and for how much it’s associated with Ansel Adams, you'd think that this was some motto he repeated constantly. That his friends would all roll their eyes and leave the room, "oh god, Ansel’s going on about making a photograph again!”. You’d think he had it tattooed on his chest. With a few buttons missing, just across his bulging pecks you could read “you don't take a photograph, you make it."

This was something he said of course, it was something he believed, I guess, but it wasn't central to anything he did.

The more I consider it, the more I think that while Ansel Adams said those words, he had no idea how far-reaching an impact they would have. It was just a clunky sentence lost among other clunky sentences.

The photography community seems to have co-opted his words and memories, making the quote what it is today. We gave it a different meaning. We completely changed the intent. Ansel Adams had very little to do with what is his most famous quote.

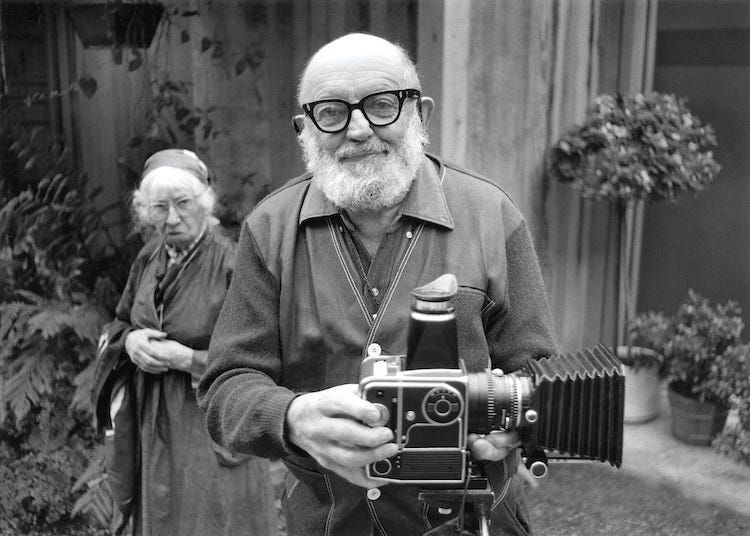

A Bit About Adams & Pictoralism

When Adams started taking photography seriously in the early 1920s, he had just missed the war going on in the art world. In the early days, photography was largely used to document things and for portraiture. It was not seen as an art, especially not on the level of painting.

Photography was a science. You needed certain chemicals in specific amounts, there were beakers and bubbling sounds, every darkroom was a laboratory. Most painters saw photography as a rigid science, not as an art. Hell, most photographers agreed.

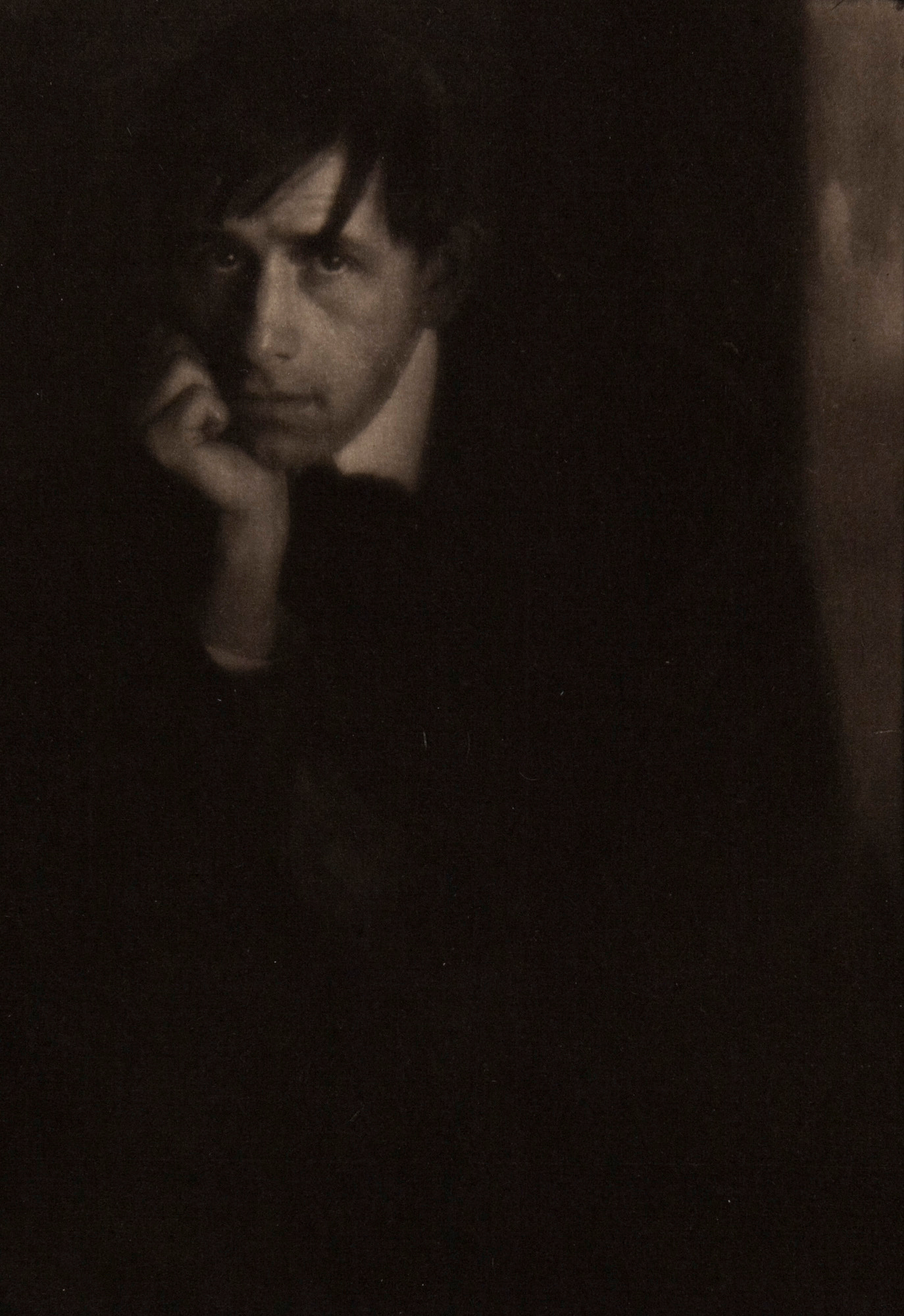

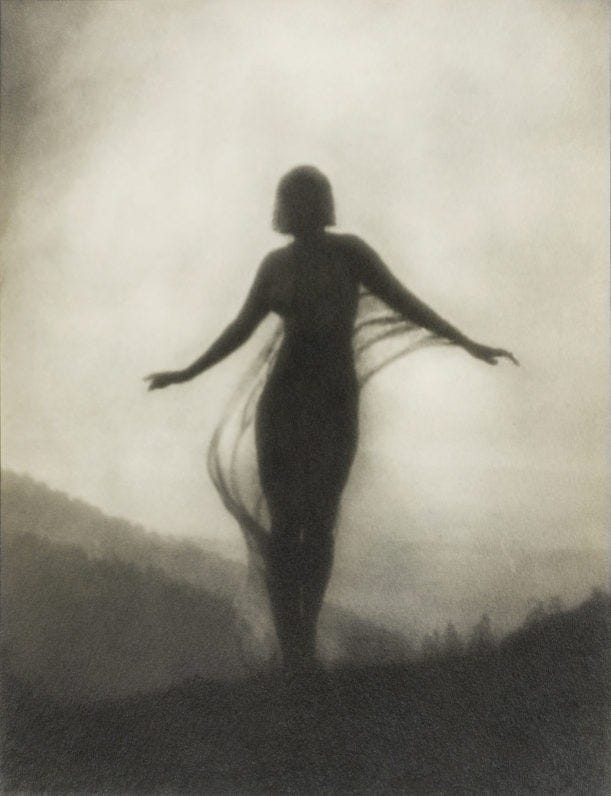

But around 1880 that started to change. Some photographers like Gertrude Kasebier, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Steichen insisted that photography was art, actually, and their style often pulled inspiration from impressionistic painters. This resulted in the Pictoralist movement, with photographs in soft focus and dream-like. Adams caught the tail end of this movement, and his early work is in that style.

While he missed the war between art and science, he was starting to wage one of his own. By the time he wrote his first book in 1935, the proliferation of roll film, retail photo labs, and snapshot cameras like the Kodak Brownie brought photography to the masses.

Now, everyone and their grandma were taking pictures. And while Adams embraced the influx of new photographers (he wouldn’t have had an audience for his book otherwise), something didn’t sit right.

Anyone could load a box camera, take a picture, drop off the roll at the drug store, and pick up the prints a week later. But what only a few could do was judge the light of a scene, adjust the aperture, exposure accordingly, load the large format camera, take the picture, develop the negative (still often a glass plate), and then make a print in the darkroom.

For most, that was impossible. To Adams, that was essential. Just taking a photograph wasn’t enough; making the photograph (which, to him, absolutely and always involved making the print) was true photography.

It’s Like Poetry, It Rhymes

In all likelihood, he used the word “make” because it rhymed with “take.” He was riffing on the expression “take a picture.” It was pretty cute of him to do so, I’ll admit. If a different word has been used rather than “take,” I can’t imagine he would have gone for the word “make.” He was taking a centuries-old concept (“taking a picture”) and turning it on its head.

When you make something, it’s a process. There is planning. There is problem-solving. Most importantly, to “make” something stresses that there is something material, tangible being made. That’s the emphasis.

In the phrase “take a picture,” the end product was assumed (a picture of some sort). The main focus, however, was upon the subject – the person having their picture taken – not the painting or, in Adams’s case, the print.

In “making a photograph,” Adams was moving the focus from the subject to the process and the result, and he spent the rest of his life writing books about just that. This isn’t surprising, coming from someone who compared making a print in the darkroom to a musical performance.

And as I said at the top, I don’t disagree with him. But that’s not how people are using the term today. The vast and wide majority of people who insist upon saying “I made a picture” might develop it themselves, but there are no darkroom prints. Even the thought of it isn’t there. It’s just exposure, development, and digitizing. Its use within digital photography is even more baffling. Nothing material is actually being made, and that is the opposite of what Adams was talking about.

The Gloves Come Off

I don’t want to ruffle more feathers than I have to here, but in my experience, most people who say they “make a photograph” are trying to set themselves apart from those who are just taking pictures on their phones. But that wasn’t really what Adams was doing. He was setting himself apart, yes, but he was doing so while teaching anyone who would listen how to, in his words, “make a picture.” It wasn’t about him being better or deeper or more philosophical. It was about teaching people how to make a damn picture. It was about the end result: the material, the print, the actual picture.

Photographers who use this quote to signify their thoughtfulness in photography use the quote thoughtlessly. We use “make” to set ourselves apart from the common folks who “just” take pictures. But why do we feel the need to do this? Why not let our work speak for itself? Are we afraid that it can’t? Are we afraid we really are “just taking pictures?” And then, what’s wrong with that?

This reminds me of being raised in a born-again Christian household. If anyone would refer to our religion as a “religion,” we’d have corrected them: “It’s not a religion, it’s a lifestyle.”

This wasn’t even pedantic, it’s just ridiculous and starting an argument for no reason. But it was done to set ourselves apart from other religions (and even other Christians). It was said to make ourselves feel superior, and more importantly, to let others know we were superior.

Why I’ll Take “Take”

Since all of this is silly and semantical, I’ll admit to you that I prefer the word “take” over “make” a photograph. Whether I’m shooting a quick shot on my phone or spending 30 minutes metering, setting up a shot, selecting a lens, adjusting the aperture, and finally exposing the film, I am “taking” a photo. If I later make a print of that photo which I took, I’ll have made a print.

But in another way, I like to use the word “take” because it reminds me of one of its earliest definitions: thievery.

On the surface, we are stealing a bit of time, we are taking the light, exposing the film. The scene before us is stolen and kept latent in the dark until we develop it. When we “leave only footprints and take only pictures,” we are very literally taking the effects of that light with us, like a sunburn on pale skin.

I’m also taking (as in learning) something from the experience. With every place I travel, everywhere I photograph, I’m gaining experience in photography, I’m being introduced to something new about the land, and I’m taking in that knowledge while I’m taking the picture.

And more thoughtfully, we are taking a bit of wherever and whomever we’re photographing with us. We carry them in our memories, of course. But we’re also carrying them in our cameras, on our exposed film.

I’m not talking about the colonial idea of the camera “stealing their soul,” but maybe it’s not too far removed from that.

When we go out photographing, especially in places we’re just visiting, we are exploiting those places for our own pleasure (and if we sell our work, for our own financial gain). Of course, it’s usually harmless, but we are still engaging in some mild exploitation, and it’s always good to remember that.

I’m not saying it’s wrong to do it. I’m not talking about obviously exploitative shots like poverty porn, photographing the homeless just because, and certainly not whatever it’s called when the creepy photographers give their naked model a camera and she poses with it sort of like she’s taking a photo, but has never actually held such a camera, but it doesn’t matter because it’s not about the camera, it’s about the naked model pretending to like photography so the creepy photographer can pretend to feel some sort of connection to a woman… whatever that is. Anyway, I’m not talking about that. That’s obviously exploitative and gross and just weird, so please stop it.

But I do use “take a photograph” to remind myself that I am actually taking something from what I’m photographing. At the very least, it’s a thought to be remembered.

Conclusion (Finally)

If I wasn’t clear before, you take a picture, you make a print. Ansel’s phrasing was fine and understandable before everyone grabbed it and turned it into some pseudo-intellectual dorm room platitude.

Ansel Adams hoped that our focus in photography would include the entire process, from the camera to the negative to the print. The entire process was “making a picture.” Because producing an actual print is so rare now, I use “make” exclusively when talking about producing the print. Using “make” exclusively for the material, the print, allows us to put more emphasis on the print itself.

Again, this is a pet peeve of mine. It’s not rational, not really. You don’t have to honor it or even acknowledge it. I fully understand that my opinion is not rational. And you didn’t have to listen to me and my dumb opinion, but here we are, together to the end.

Share this post