I have not picked up a camera yet this year. My last photo was taken in a cemetery on New Year's Eve. I don’t miss it, and I don’t worry that I may never pick one up again. I’m fairly certain I will, I’m a photographer, after all. What I also don’t worry about is inspiration.

The way I shoot is much like a travel photographer on assignment. I rarely touch a camera if I’m not on the road (at least a daytrip), and I’ve never worried that I won’t be inspired to photograph once I leave town. It’s just not something that crosses my mind anymore.

But it’s late winter, and a lot of photographers start getting a little worried that they’ll never photograph again, that nothing will motivate them to look through the viewfinder, that nothing will inspire them. And that must be a little terrifying.

I know it is. I used to live with that fear, especially in winter.

For many of us, we spend the spring, summer, and autumn with cameras in hand and backlogs of film piling up to develop. We share our weekend trips on social media the week following an outing, and then do it all over again.

But when winter comes, we rest, like it’s natural for us to do. Our time with the camera lessens or even stops. Most terrifying of all, we run out of things to share on social media. And then we panic.

This can easily be blamed on social media, and it’s certainly exacerbated the problem. But this drive not to create, but to produce has been around since the first artist showed a painting on a cave wall and was asked “this great, Ogg, but what you do next?”

Art and consumption have always gone hand-in-hand, but art and consumption are blood enemies, as they should be. Is what we think of as our lack of inspiration actually just fear that we have nothing to produce, that we have no product? Maybe. We’ll get there.

But first let’s make sure we’re on the same page when it comes to inspiration. A lot of times when we talk about it, we’re actually talking about motivation. There are entire books written about the differences, but essentially, motivation is usually an external force driving us towards a goal. It’s almost transactional, but not in a bad way. Maybe we’re motivated to do a project or make a zine, or even finish a roll of film. Inspiration is internal, it comes from within ourselves. It’s often spontaneous and unpredictable, which renders most advice about it sort of pointless.

The word “inspiration” originally came to us from French where it meant “to breathe air into.” But in English, it was first used figuratively: to infuse thought or feeling into a person so they could create. It figuratively meant to breathe in creativity. Naturally, with all that creativity in our figurative lungs, we couldn’t help but make art. Literally.

Is this why it feels like we’re suffocating when we can’t find our inspiration? Is this why it feels like we’re dying? Is this why we’re willing to believe and follow almost any advice in some hope to breathe again?

I love the metaphor. Art is life and inspiration is breath. It just feels so perfect and wonderful. But I think it lends itself to bullshit. At least, that’s the feeling I get when I read articles or watch YouTube videos about finding your inspiration.

One article I came across on a website aimed at “creative professionals” and photographers specifically was a scattershot list of disconnected ideas that require a lot of inspiration to even work up the motivation to do.

Things like: “Experiment with Different Genres” and “Do Something Differently” and “Do a Personal Project.” They all seem like they were written by someone who forgot what “inspiration” was.

The videos I’ve come across are all nearly identical and pretty useless if you’re suffering from whatever we call the photographer’s version of writer's block. They seem to blame it on impostor syndrome — the feeling that you’re just not good enough — and their advice is “try a bunch of different genres” which they then list. And then the video ends.

But I don’t think lists are a cure here. I don’t think we can rattle off advice like “Find Inspiration in Nature” and be done with it. I think it’s lazy and useless.

There’s one bit of advice that drives me insane, and this could absolutely be my bias showing, but it’s “buy more gear.” I cannot stress this enough - it’s not your gear. A new lens is not going to reignite your lost inspiration. If one does, you didn’t lack inspiration, you lacked drive or were just bored and that’s not the same thing.

Much of the other advice seems to be grasping at straws just to have something to talk about. “Shoot a specific color,” one reads. “Try a new focal length,” attempts another. I suppose they mean well, but have they ever talked to someone actually suffering from lack of inspiration?

They probably think they have. And that’s because as soon as we feel ourselves take a pause, we assume we’re losing something. We really aren’t, we’re just breathing in. It’s not even a rest. And that’s why these throw-away bits of advice seem to work: they’re not for people actually lacking inspiration. They’re written for people generally new to photography and uncertain what to photograph next. And that’s okay, but it’s not what we’re talking about.

I really hate to say this because it sounds dickish and pompous, but I think there are two kinds of photographers (at least). One whose primary focus is usually upon photography, and the other whose primary focus is usually upon collecting cameras. There is some crossover, of course, it’s sort of a spectrum, but I think this sums it up. And both are equally fine. There’s nothing wrong with treating photography as an art just as there’s nothing wrong with collecting cameras.

When it comes to inspiration and being desperate for it, the lack of it is like gasping for air. This whole metaphor probably applies more to the photographers who lean more towards the art end of photography. It goes with the territory. It’s not a badge of honor or anything to brag about. It is what it is.

Most people whose focus is upon collecting cameras and buying new gear don’t have to think much about inspiration in taking a photo. And that’s okay. That’s not their primary focus. Again, they’re not who we’re talking about.

And to be fair, I have come across some actual useful advice. Some folks say to look at other visual art apart from photography, or at the very least look at photos that look nothing like something you’d normally take. Others say to find other photographers and try to talk it out if you can get around the gear talk. I think finding a few photographers who are also friends can help immensely. I’ll never downplay the good effects of having a community.

A few also suggest “taking a break.” This might seem like shit advice since you’re obviously already taking a break because literally nothing is inspiring to you, but it really is good advice if you go into it properly.

I take a break every winter. It’s just part of my schedule. I don’t worry about it. I don’t fear that I won’t come back. I don’t really give it much thought anymore. I don’t give it any power over me. I am taking the break on my terms, not out of lack of inspiration, but because I’m stepping back for a time.

I’m still a photographer; I still love photography. I still think about it constantly. But I’m just not doing it right now. Even if it coincides with a lack of inspiration, take your breaks on your terms. Get that rest, that separation. Don’t concern yourself with coming back. And maybe, if you’re brave enough, be okay with never taking another photo. It’s a weird detachment, but if you need to go that far, go that far.

But here’s the thing about inspiration, the thing that the articles and videos won’t mention: I can’t tell you what to do to get inspired. Nobody can. We can throw out ideas and, sure, something might be jogged inside of you, but that inspiration has to come from yourself. I know it’s not what most of us want to hear, but what inspires me to keep going will not be what inspires you to do the same.

Oh, but this doesn’t mean I don’t have my own advice! We’ve come this far, did you really think I was just going to drop you off here? In this economy?

My advice is to question yourself. Why do you want to be a photographer? This isn’t an easy question. Answering “I like photography” isn’t going to cut it. Why do you want to do this?

This is not asking “What do you want to photograph?” or “What do you want to get out of photography?” Those are about the product, about motivation. We’re not talking about that. We’re talking about: why do you even want to be a photographer?

The answer might not even be something you can put into words. And to be honest, I’m not sure words are the best way to express this. Think about this. Picture how you’ve worked in the past. Remember setting up shots, remember how you framed and composed something.

I’m not asking you to look at your old work, though that’s often some of the better advice, and feel free to follow that at some point. But that’s not what I’m asking of you right now. Forget about the product, forget about the photos, the books, the zines, the prints, the projects for now. Why do you want to be a photographer?

Why do you want to pick up the camera? What was so deep inside of you that only a camera could find it? Why do you want to be a photographer? Why not a writer? Why not a painter? Why not a musician? What can’t those arts give to you what photography can?

When people come looking for inspiration, I understand that they’re not also looking for an existential crisis. But if inspiration is the air that we breathe in, a lack of it is literally (well, figuratively) existential. It’s not something that can be brushed aside with “buy a new lens” or “try being a street photographer,” it’s far more important than that. It deserves to be treated with all the respect that deeply questioning yourself and your motives entails.

If you are in a creative rut, it’s something you’re going to have to work yourself out of. Nobody can guide you out. We have various influences and muses, and they will come back into this at some point. But first, you need to figure out why you’re even here. You need to figure out why you want to be a photographer.

But is this even enough? No, probably not. And that’s okay. Your inspiration will probably come back. These things come and go now and then. It’s okay now and it will be okay in the future. But you need to be okay with it never coming back. I realize this is a bit tricky if you make a living off of your photography. But then, that’s the hazards of commodifying your art to the degree that you must produce to survive. That’s on you for better or worse.

Still, you need to be prepared for the fate that your art might lie in a different medium, or even several different mediums. Maybe you’re not a photographer anymore. And that’s okay, too. Anything that happens here is okay. Your identity isn’t as a photographer, your identity is you, an artist. You expressed that art through photography and you likely will again. Or maybe you’ll move on. But either way, you are still you. Your thoughts and dreams and creations still matter. That air of inspiration still matters. It will come again, and you will breathe it in, and something beautiful will come out.

Will you still be a photographer? Maybe. Hell, you’re here, so probably. But first, you’ll need to sort this out: Why do you want to be a photographer?

Etymology: Emulsion

To photographers, emulsion is that thin layer of something on top of the film base. It’s a mix of gelatin and photosensitive crystals. In my other life, I’m a screen printer. We also have emulsion. It’s a thick oozy photosensitive liquid we coat on the screens we use for printing.

So does emulsion mean a photosensitive layer? No, it’s got nothing to do with that, both things just kind of the same thing.

That photosensitve mixture was first called “emulsion” in 1840 by John Herschel, an early chemist and photographer. He invented the cyanotype and did extensive experiments with emulsions made of plant matter (he called them phytotypes). He was also the guy who (probably) coined the term “photography.”

While Herschel was the first to use emulsion in a photographic sense, he didn’t invent the term. Emulsion was handed down from Latin ēmulgēre, which was a verb meaning “to milk out.” It would have been used when talking about milking a cow or getting milk from nuts.

In fact, the first known English use of emulsion was in 1612 and was about an “emulsion prepared of almonds.” And for the longest time, that’s what it meant — “A milky liquid obtained by bruising almonds, etc. in water.”

Within a few decades, the definition expanded to include any nut or seed or kernel, but it also took on a metaphorical meaning. In 1658, Dr. John Robinson, whose father kind of started the Pilgrims in England, wrote a long-winded book about Truth called Endoxa. In its fourth damn preface, he wrote, “My wished end is, by gentle concussion, the emulsion of truth.” Meaning the essence of truth. He seems to have been the only one to use it that way.

Anyway, before being used for photographical purposes, the pharmacological definition widened further to “a milky liquid, consisting of water holding in suspension minute particles of oil or resin by the aid of some albuminous or gummy material.”

And Herschel’s use of emulsion won out. Other words like “collodion,” “silver bath,” and “sensitizer” sort of have a photographically similar meanings, but are actually different things requiring different words.

The way we use emulsion now is almost a synonym for brands and lines of film. “What are your favorite emulsions,” someone will inevitably ask me, mostly because asking “what are your favorite films” will start a whole conversation about Akira Kurosawa, which is probably much more enjoyable.

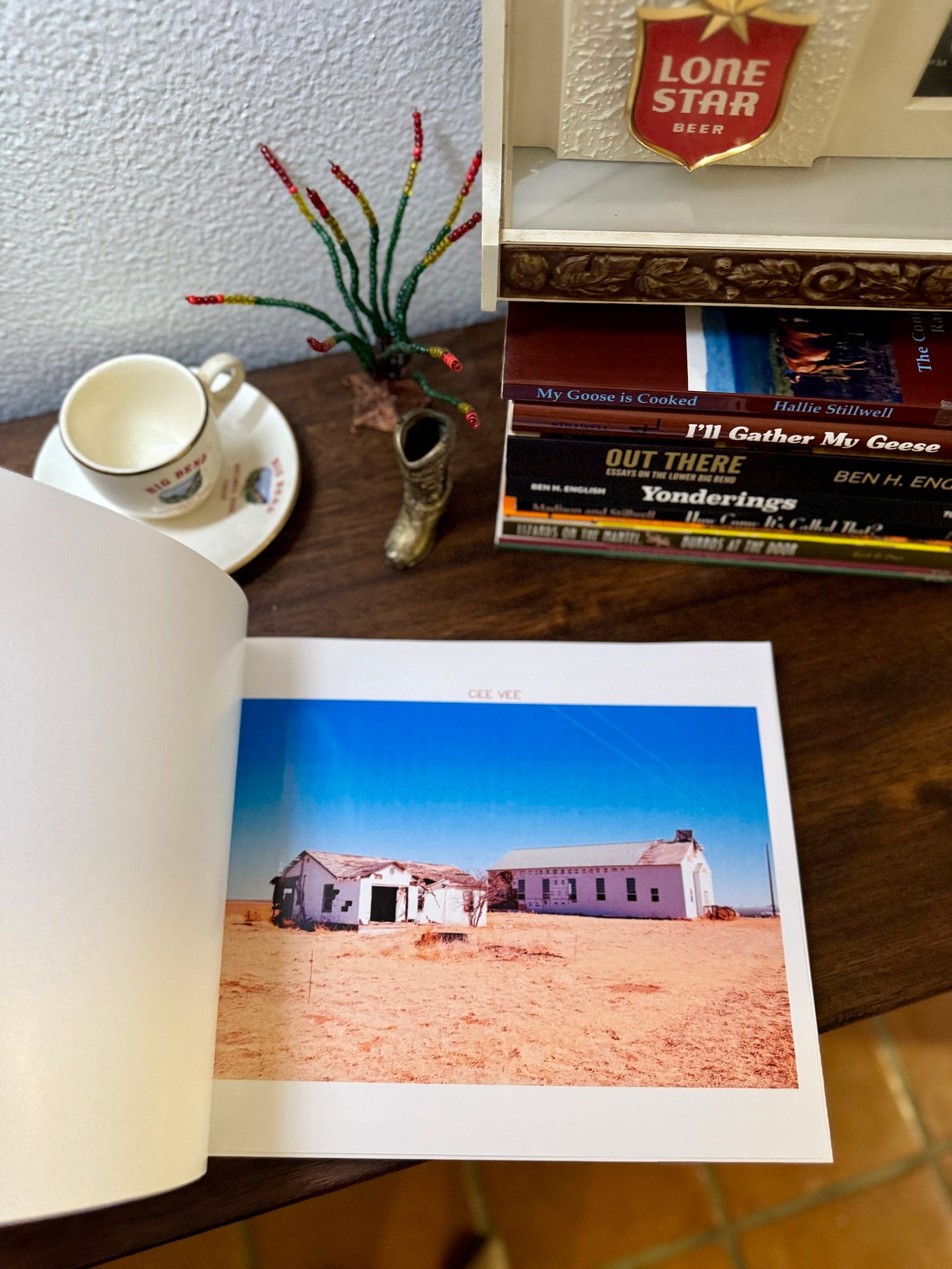

Review: Texas Textures, Vol. Two

For me to connect with a photography book, I have to feel some sort of connection to the photographer. This doesn’t mean we have to be friends (though in this case, we are), and it doesn’t mean that I have to love the photographs (though in this case, I do). But one of the things that can connect me to a book is a sort of kinship. Sometimes that kinship is parasocial — I don’t typically know the photographers, hell, often they’re not even alive.

In the case of Kat Swansey’s Texas Textures Volume Two, that connection comes from how we travel. In her Preface, she writes: “For me, these trips are deeply intimate, I travel alone and rarely let others in on my adventures. These trips are a way for me to make time for myself. To see something new, ponder life’s mysteries, allow myself to escape the hustle and bustle of city life, heal what ails me, or just sit with myself — whatever needs to be done at the time.”

We don’t photograph in the same way. If we visited the same towns (and in this case, we have), our photos would be night and day. But why would I want to look at a book full of photos like those I would have taken?

Many folks who photograph old towns and buildings (and especially signs) spend a lot of energy lamenting the disappearance of these things, like we can somehow restore and preserve everything pre-1960 in perpetuity. Kat, on the other hand, has a reverence for these places, but isn’t trying to bring back some bygone glory days.

It’s not that she’s not sentimental in her photos and writing, the book is filled with it, it’s more that she is presenting her Texas on her terms while also allowing Texas itself to exist as it is.

There are various stories she wrote and placed throughout the book detailing her travels and some of the history of some of the towns she’s sharing with us. This gives it a broader idea and helps place you at her side as she travels.

The photos themselves — over 300 of them taken in 34 towns! — are very matter of fact, color images, showing the age and weariness of these towns. She presents each place like anyone might see it if they’d only look. These are taken from sidewalks and roadsides, each photo accessible and open.

There are almost no people in Kat’s book. And yet, it’s a story of the people told through the town and homes, buildings and storefronts they left behind. She photographs the vacancy remaining with empathy and understanding. She’s not just passing through, these are her places, her towns, and her Texas.

Texas Textures Volume Two is the follow up to Volume One, which she released in 2022. They are very much of a piece. If you have Volume One, getting Volume Two won’t feel redundant. Her shooting style over the few years has evolved in some subtle ways, and this new book is a great step forward. Treat yourself to both.

I cannot recommend this book enough, so do pick it up. You can find copies of it at katswansey.com.

Share this post