If you look through my photos, you will see pictures of abandoned buildings, of houses left empty, of roads seldom driven, of paths sometimes walked only by me. You will see endless photos of old towns, empty cars, power lines, bridges, and railroads. But you'll almost never see a photo of a person, let alone a portrait.

It took me years to realize that I shied away from this. And maybe that's what it is, maybe I am shy. Too shy to ask if I could take your picture. Too shy to learn just how to make it good. Too shy to extend myself to make that connection.

But part of that realization was that while I don't take pictures of people, I do take pictures of humanity, though maybe that isn’t the right word (as you’ll see soon enough). Maybe I take photos of personality.

People

When someone first pointed out that I didn't take pictures of people, I almost didn't believe them. I will roam from town to town, taking many photos, talking to many people, seeing them on the streets and in their cars and in their houses, and yet, rarely have they ever appeared in my photos.

All of these subjects, all of these places that I photograph, were once peopled, were once inhabited. Some still are. Nearly every photo of mine has some record of human interaction with nature.

I have fallen in love with this interaction, this relationship between humans and nature. I don’t even look for it anymore, I just see it. In every place I visit, every photo I take, there it is.

I used to submit some of my photos to an online group that focused upon nature photography of Washington. Their only rule was that there was to be “no hand of man” – obvious evidence of human occupation or manipulation. But almost everywhere in Washington, almost everywhere in America, you can’t find what we think of as nature without the hand of man.

The trails we walk, the hills we climb, the streams we swim were all affected by this mysterious “hand of man.” Perhaps it’s not so obvious as a paved highway through a forest, but the lasting ramifications of our relationship with nature are everywhere.

Nature (Animals)

Our usual definition of nature is anything outside of human interference. It’s tempting to suggest that our view of nature is faulty – that maybe humans should be counted as part of nature rather than separate. This makes sense in so many ways, especially because of how we now build our houses, our cities, exiling nature to the outskirts, and well-managed parks.

But in another sense, maybe it's our perception of people that is faulty. Our idea of personhood and personality is very narrow. We see ourselves in it, of course, and sometimes we extend it to our pets, which is understandable. But almost never does it cross that line, almost never does it leave our house, our property, our bubble.

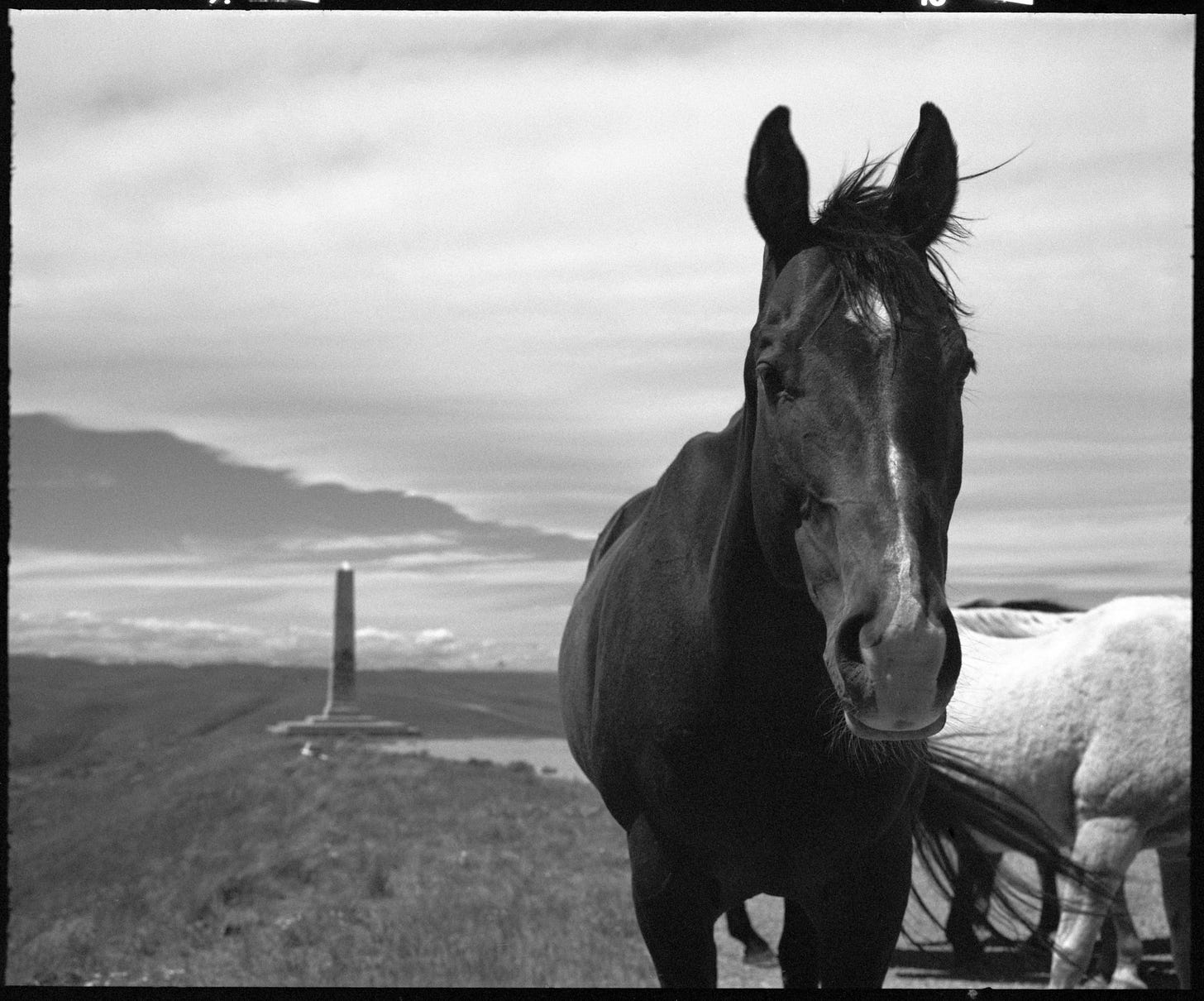

And yet, it shouldn't be a stretch to see other animals as people. We give names to our pets. We see the personalities in our cats and dogs. And so it shouldn't be insurmountable for us to see the animals we come into contact with in the same light. Maybe we aren't as familiar with their ways, but we could be. There's very little stopping that from happening. Maybe it’s our shyness. Maybe all of us are as shy with the animals as I am with people.

I don’t take too many photos of animals, if I’m being honest. I shared a couple of stories not too long ago about photographing some cows. I’ve also photographed a bird or two, when I got the opportunity. And, of course, there are the photos of Juniper on her deathbed. It was a devastating honor to take those photos.

I do wish I could take more photos of animals, but it isn't shyness that's stopping me, it is skill and maybe patience. I don't have the patience to be a wildlife photographer. Also, most of my lenses are wide. In many photos, there must be hidden animals, unseen, staring at me, wondering what I am doing with a 90 mm lens. If only they could tell me.

Nature: Plants

But why not the plants? In some narrow ways, we are familiar with seeing plants as people. We raise and talk to, and even name, flowers and ferns. There was a prayer plant who lived in my house, and his name was Greg. I didn't name him, but he came to the house with that name, and it stuck.

Many of us fawn over the flowers and vegetables growing in our gardens, and we form what logic tells us is a one-way relationship with them. But somewhere inside, we do understand that there is an exchange happening. Even materially, we water them, they grow, in return, they make us happy and fill our stomachs.

So why not the plants in the wild? Why not the trees, the grasses, why not the wildflowers and sage? Even in the cities, plants are more plentiful than our human neighbors. And they're often much easier to deal with.

Other People

I don't think I've always seen plants and animals in this way, but I'm having a hard time remembering when I didn't. It's something that I simply haven't given much thought to. But when I look through my photos, I can see it’s there. I am, in a way, taking photos of people. Maybe they aren't human people. And many of them aren't animal people.

But I take portraits of trees. I focus in on flowers. They are not, as we often mistake, inanimate objects. They have life in them. They cycle through birth, disease, and death the same way we do. We have much more in common with them than we do a house, or a bridge, or a car.

There is a world going on around us, under our feet, above our heads, and in some ways, we are connected to it. But in most ways, I think we've neglected it. Maybe we’ve forgotten. Maybe we've never had it.

When we were babies, did we really see much of a difference between our older sibling and the dog? Didn't we have a favorite tree? Didn't we have that childhood urge to run to the forest?

I was fortunate enough to grow up in a small town surrounded by farmers’ fields and woods. A large creek bordered one side of town, and I’d spend entire summer days running through the trees, scrambling up hills, building forts, and catching turtles and bugs.

I learned quickly that if I sat silent and still, birds and squirrels would get used to me, ignore me, and go about their normal business. There were special moments when I’d see deer creep close for a drink, eyeing me all the while. And even when the deer and the squirrels weren’t around, I discovered that I could sit by a stream and just listen to its murmuring.

Our Inanimate Friends

So really, why stop at plants and animals? Couldn't the water also be a person? It can be calm and still one day, and full of anger and violence the next. We see that in ourselves. We see that in animals. And we can see that in the rivers and streams, the ocean, especially. None of these beings is inanimate.

Even the rocks, though they are still and solid, are not inanimate. It may take millennia, but they can move. Even mountains can move. There is a mountain in Washington that many geologists are starting to figure out that moved from Baja California. In fact, much of Washington state is made up of tiny islands that were in the Pacific Ocean. They've all gathered together to make the home where I live now. And yet we think the land is inanimate because our lives are too short to see its motion.

Nature Is Motion

As photographers, we can show the personality of animals and plants, of water, and even mountains. And I've always found it important to do so.

Many photographers who photograph nature refuse to take their pictures when the wind is blowing. They want to take a beautiful photo, with a tight focus and a wide aperture. They want a tripod and the fastest shutter speed to negate any movement. I never understood this.

All of nature is in motion. All of life is in motion. Even in death, we are still moving, the bugs wriggling around in our bodies, the worms in our guts. It's all motion. There's no way to escape it. As photographers, why are we trying to deny this?

When I take a photo of, for example, an abandoned house, I try to show the uniformity it has with the nature around it. I try to show how it has changed and bent to the landscape. But I also try to show that everything around it is in motion by letting the shutter linger open for a second or more. I'll wait for a breeze if there is no wind, I will watch for the grasses swaying, and the tree limbs moving, and then I will open the shutter and wait, capturing more than just a quick sliver of light. I'm capturing a moment. I'm capturing a period of time, an era.

Maybe all of my photos are motion pictures, in this way. But it's my way. I've only ever done it like this. I love seeing the movement. I love being reminded of how the stream is alive, the grasses are living, the leaves in the trees are waving. The blur that is present on film represents the opposite of what most nature photographers are trying to capture.

Most nature photographers take after hunters, seeing something in the forest, a flash, and firing their gun to stop it. In fact, this is where the phrase snapshot was derived. Originally, it was a hunting term.

But I long for the opposite of this. I go to nature to observe it, to live in it, and, as a photographer, to bring a little of it home with me. Not as a taxidermied trophy on film, but as my memory holds that moment. I want to capture how the moment felt just as much as how the moment looked. But still, nature photographers who freeze time with no movement at all fail to do this. They fail to move me.

Home and Homes

This isn’t to claim that I never take photos of solid architecture, divorced from any nature around it. I do, and I enjoy that to some lesser degree. I take photos of signs, of cars, of human-built things, like any other photographer might. And yes, you can see the humanity in those things. But they are, without a doubt, things.

More importantly, they are commodities. While there might be some artistry in there, they are, in the end, made to be sold. They are products in the grossest sense of the word. Even adding what little twist of artistry with the camera that I might, there is a deadness to them that nature can't match.

This is why photographing an office building, a sign, a car, or a store is different than photographing a house, a home where a family once lived. And yes, there may be some small evidence of human interaction that is still held in an abandoned storefront. After all, people spent their days here, making something close to a living, trying to keep their families alive. But it's just not the same; it was not a home.

Our homes, in some ways, are the closest thing to nature that we have. We build our homes with our families, both blood and found. This is not any different from birds with their nests and rabbits with their warrens.

Sometimes we mistakenly say that all of nature is their home, meaning the entire forest or the entire prairie is the home of all of the birds and animals who live there. In a broad sense, that's true, but really, most have established specific homes, just like us.

Once, when I was walking through a canyon floor covered with sagebrush, a coyote darted out in front of me, scampering off to the cliffs above. A few more steps, and then another coyote started from behind the same sage, running off a few yards, watching me.

Several more steps and heard their pups, nestled and snug under the shade of a large sagebrush, with grasses and weeds surrounding it, hiding it. I had startled the mother and father, and they bolted out of instinct. And stopped, remembering their young, hoping that I would not hear the helpless cries of their pups, and if I did, praying that I might pass on.

As much as I wanted to look in to see them, in all of their adorable glory, I made my way quickly out of the canyon, away from their home, which I had unknowingly invaded. I didn't stop to take a photo. Even though I wanted to, I could feel the fear of the parents. I could understand that, relate to that. And I wanted to take away the fear that I caused as quickly as I could. I wanted to make things right again for this terrified family. So I did.

All of the nature that we see, all of the forest and the fields, is a world that contains a multitude of homes for a multitude of animals. They may have specific homes, but all of nature is their country. And we are in it, too.

It’s Not Isolation

Lately, I have been rethinking my defensive stance on isolation and solitude. I once wrote that solitude was “that moment you realize you are alone, that there is nothing that will touch you.” After being in the city for so long, I wrote that “I craved isolation, that chance for solitude.”

Of course, I understand what I was trying to say – simply that I needed to get away from people, from humans specifically. And I still feel that way, though maybe I should try to embrace this desire less than I do. Is this truly the mentality I should be encouraging in myself, in others? Shouldn’t I be striving for community?

Unless we are enclosed in a windowless room, we are not isolated. We are never isolated. All around us are the animals, the plants, the rocks, the streams. We are never alone, and if we feel that we are, perhaps it’s our perception of self that needs to change.

This is why prisons are so dangerous to our society. As punishment, we subject our fellow humans to real isolation, to real solitude. This is somehow supposed to be justice; it is supposed to teach some lesson. But in the end, it is all just our petty revenge. We know exactly how to hurt our fellow man, and we do it joyously; we do it jokingly. As a society, we revel in our imprisonment, we profit from it, we create laws and situations to imprison specific cultures present in our society. Prison is a quiet genocide.

Eve

We know this, and it is our fault that we are not changing this, but also, it’s no wonder at all that we have gone down this path. The past 2000 years of Western culture have seen us moving farther and farther away from nature. Our teachings, mostly Christianity, have formed our cultural relationship with nature. We are told that we have dominion over the earth, over plants and animals, even over women. It is impossible to form a healthy relationship with that as a foundation.

Our own creation myth involves the first man and woman, Adam and Eve, as one with nature until Eve longs for more knowledge and they are both exiled from this oneness, from nature. Our cultural introduction to nature then, is that of an exile from it. We are automatically estranged by this punishment, by this petty vengeance.

It’s no wonder, then, that we turn this on ourselves. It’s no wonder we feel disconnected from nature. It’s no wonder those few who have remade this connection with nature were often seen as witches and of the devil. It’s no wonder that we created industrialism. No wonder capitalism. No wonder the times in which we live.

All of this is taught to us by our parents and elders. As children, we are born with an understanding of right and wrong, we even have a sense of justice. But revenge is something we must learn. Dehumanization is something that must be instructed.

We are taught that our fellow humans are worth nothing if they can’t produce, if they can’t serve us. We have turned ourselves into assets and products, into elements of wealth; this is perhaps the most complete dehumanization.

Thievery And Healing

So what chance is there for the beings who are not humans? When we view animals and plants and forests and rivers as commodities and products, we are robbing them of their nature. We are literally stealing nature from them. And as photographers, if we see them as only products to be managed, to be captured, then that is how we will photograph them.

If we treat these subjects inhumanely, we are also robbing ourselves of our own humanity. We are dehumanizing ourselves while we denaturalize nature.

If we do this as photographers, our lens will only see this distorted view. What we capture on film will only be an imitation of what we should be seeing, what we should be feeling. Our subjects, our art, and our world all deserve much better from us. We ourselves deserve much better. We deserve not to be severed from our larger world, from nature. That connection we may have had as children, or that bond we had before careers and obligations got in the way, is vital.

There is a healing in this connection with nature. No, it doesn't take the place of hospitals or therapy. We have all seen the meme of a picture of a forest with the words "real therapy" underneath it. That's a lie, and it's a misrepresentation of nature. It's a misunderstanding of our relationship with the natural world. It's also a misunderstanding of our brains and therapy in general.

It's always good to remember that “natural” doesn't mean healthy; after all, a bite from the Western rattlesnake could be deadly, but it is very natural. There is an array of plants, like death camas, who live in the canyons of Eastern Washington, who can kill you in a very natural way. Their bulbs are strikingly similar to wild onions. Cooking them doesn’t tame the toxins, and eating just two of the bulbs can kill you.

But nature, or rather, our relationship with nature, can be restorative. Meaning that our return to nature, our regular interaction with nature, can help us recover and adapt to the unnatural demands of life. It’s been shown to boost our positive moods and self-esteem. Study after study shows this.

It should also, however, be obvious. How many of our stressors and irritations come from the world that we built to keep nature out, to keep it at bay, and under control? We have created some really wonderful things, but there is a price to pay.

For many of us, making the re-connection isn’t so easy. Most Americans live in cities. While there is nature there, of course, a green belt isn’t a forest. A park isn’t a prairie. These spaces between asphalt streets and sidewalks are important, but they are not wild.

What About Photography?

In the notes that I took while jotting down my thoughts for this piece, I wrote, “What does this have to do with photography?” I even circled it! After my last episode, where I escaped into the wilderness, leaving the camera at home, I’m not sure what it has to do with photography specifically, but I know that I need to change how I approach photography because of this.

Even though I am often able to escape the city to wander in the wild, I want to do more than just wander. Wandering is really just mindless walking. It’s nicer to do in nature, but honestly, it's not that much different than mindlessly wandering around anywhere. I want to take time to be still in nature. It’s the stillness that I’m missing.

I want to first be still in nature, to be still amongst the wind and the blowing grasses, the swaying leaves, and rushing water. I want to be still the same way a musician waits, listening to the rhythm, listening to the beat, waiting for her time to jump in and move with the music.

By the time you hear this, I may already be on the road. I have somehow been fortunate enough to arrange my life so that every year I can take a month off and travel. I generally camp and photograph back roads and small towns. I favor the grasslands and prairies of the plains. It's not where most would choose to vacation, but then, this is hardly a vacation.

In past years, I would wake up before dawn, working with my camera until sunset. I had almost no downtime. Everything was a rush, everything was frantic and left little time for stillness.

My mind was a whirlwind, a tornado exhausting my body, chewing up the miles, and always feeling like I was running late and that there was never enough time.

This year, I hope, will be different. This year, I went to focus on being still and listening. The camera is, essentially, superfluous. I will photograph whatever is in front of me. But I want my approach to those photographs to reflect everything I have said to you today.

I am shy when it comes to photographing people, and maybe less shy with the non-human things I photograph. But there is still much work to be done.

I will still visit these places that were once inhabited, and I will still photograph them, purposely trying to recover their humanity, their population. I'm not sure that the problem is my photography at all. The camera allows me to make this connection to the wider world, to nature. It allows me to see the humanity in the abandoned homes, the ghost towns, the places where our fellow humans lived and loved.

My camera, or rather, me when I am behind my camera, can see all of this. But without the camera, I am almost blind to it. And that is something that needs to change. That is the thing that needs stillness. Not the stillness of nature – nature is never still – but the stillness of myself that is impossible in a city that’s constantly tossing me around. This need to still myself is the thing that I have mistakenly called a need for isolation and solitude. It's a small error, perhaps, but it feels good to correct myself. I was wrong, but I think I'm on a better path now.

For this trip, I want to slow down. This may mean fewer miles, this may mean broken plans, it may even mean fewer photos, but it will also mean that I remember them all. I will remember every blade of grass, every breeze, every movement around my stillness. And maybe, if I'm fortunate, I'll remember to let go, allow myself to drift into the music, into the wind, into the rushing current to be pulled along or finally pulled under.

Share this post